Improving chemical hazard testing for endocrine disruption

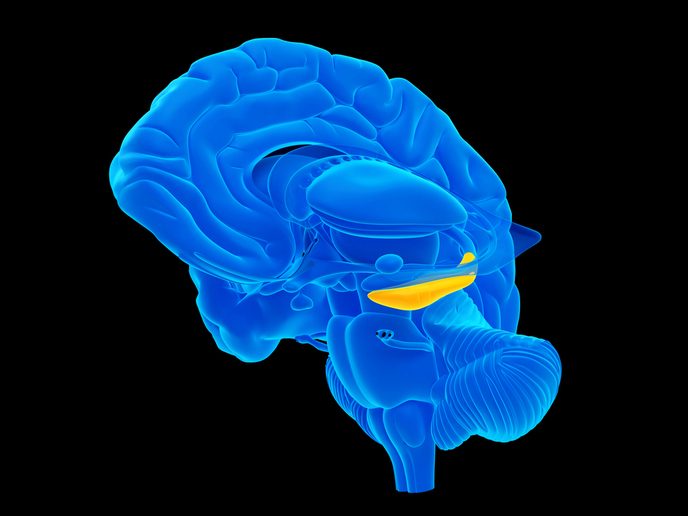

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are chemicals of concern because they impact humans and animals by blocking pathways between hormones and their receptors. This can cause over- or under-production of a hormone. EDCs can also mimic hormones which then makes the body’s reaction inappropriate. Currently, EDCs are identified separately for human health and for the environment, and there are different approaches to testing for these, dependent on specific legislations. Chemicals aimed at protecting plants, biocides and industrial chemicals are all subject to controls by various bodies, such as the EU and its Regulation on the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH). In some cases, a chemical might fall into two usage categories and so be analysed by two different organisations. When it comes to human health, testing systems mostly depend on rodent models, while, for the environment, fish and amphibians are commonly used. “Because of the clear similarities between the endocrine systems of humans and other vertebrates, it would reduce the number of animal tests and improve the efficacy of chemical hazard assessments if the data from human health and environmental testing could be combined,” explains Henrik Holbech associate professor and research group leader of Environmental Toxicology at the Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark. With support from the EU, Holbech coordinated the ERGO project, which used the thyroid hormone system (THS) as a ‘proof of concept’ to show the benefit of combing the data. “We wanted to break down the wall between the different research fields in order to develop a standardised way of using data and to improve the existing set of testing guidelines, to benefit the environment and human health,” he adds.

Developing new tests that can be applied to fish, amphibians and humans

The first thing the team needed to establish was a detailed understanding of the mechanisms underlying the interference of chemicals disrupting the THS, to compare the results across vertebrate classes. So the team tested chemicals known to affect the THS – which they called ‘model chemicals’. As Holbech says: “These model chemicals were tested in a lot of different methods and assays including cell-based assays (in vitro), in the embryos of zebra fish and the African clawed frog, and juvenile mice.” To get the human profiles, the project also analysed the presence of the chemicals in mothers and their children. The process was far from straightforward. Some of the tests had not been developed to test THS disrupters. “We had to overcome this challenge and develop a new set of tests and markers for fish and amphibians that could also predict effects in humans,” notes Holbech. This was successfully achieved, and the most relevant are being shared with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which is currently producing a global standardisation of test guidelines to assess the hazard of chemicals.

15 laboratories from three continents producing new guidelines

ERGO developed new in vitro assays and identified novel chemical outcomes – ways of assessing the impact of a substance on humans, fish and amphibians. But the methods are of no use without a means of applying the data collected as a result. So the project also developed networks called Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs) to enable the use of fish and amphibian data for human health and vice versa. As one of the final tasks, the team published a guidance document on how to extrapolate effects between vertebrate classes. They have also presented the ERGO strategy for stakeholders controlling the relevant legislation such as the European Food Safety Authority and European Chemicals Agency, to maximise the impact of the ERGO findings and approach. Holbech looks back at the project proudly: “The collaboration among the 15 partners was really encouraging, and we produced significant results that will increase the protection of humans and animals against EDCs.”

Keywords

ERGO, chemical hazard testing, endocrine-disrupting chemical, EDC, REACH, new tests, fish, amphibians, humans