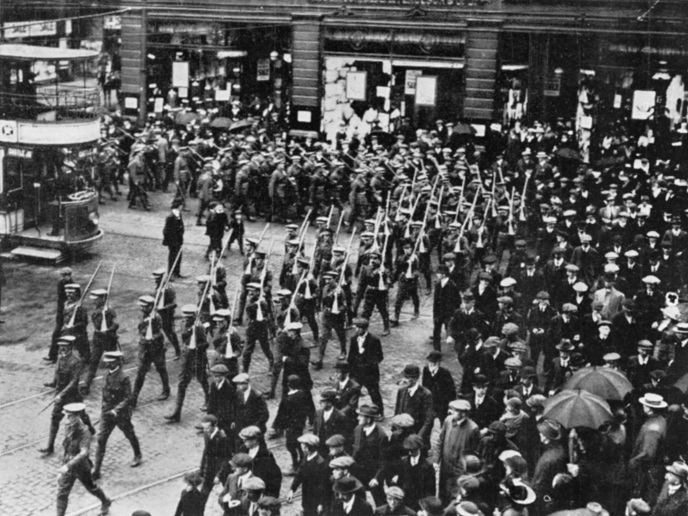

Pre-war Europe: gathering in arms as a daily experience

Organised political violence and armed associations before the Great War has been largely understudied. “This is mainly the result of an underestimation of the role played by organised violence in pre-war Europe. The Europe of the so called Belle Époque was actually a continent in which the practice of organised violence was a daily experience for thousands of civilians,” explains Matteo Millan, coordinator of the EU-funded PREWArAs project. In the context of this, PREWArAs set out to provide a comprehensive, multiscale overview of armed organisations in pre 1914 Europe by studying a wide array of different armed associations that spread and developed across Europe.

The gathering in arms in Belle Époque Europe

The lawful gathering in arms within armed associations was a mass phenomenon, which involved thousands of people in Europe. “Actual paramilitary groups such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (100 000 men in 1913), long-established militias like the Somatén armado de Cataluña (40 000 members), private police forces like the German Zechenwehr or the British Volunteer Police Force, as well as the myriads of training groups and shooting clubs, such as the Volunteer Cyclists and Motorists in Italy, are just a few examples,” notes Millan. Some of these groups aimed to provide a response to the increasing influence of mass politics. “These groups resorted to the use of weapons and firearms as a legitimate means of political action and social cohesion. They also took advantage of the rule of law, and therefore, their existence and right to bear arms was guaranteed by state laws,” adds Millan. Armed associations in pre-1914 Europe emerged at a time in which polities in Central and Western Europe were acquiring a truly modern character, and national armies and modern police forces had become the norm. “In a nutshell, armed associations embody the dark side of the Belle Époque for two reasons. First, because they are a historical phenomenon, which has never been investigated before. Second, they encapsulate all the contradictions of the period, which was torn between powerful processes of democratisation and authoritarian temptations,” outlines Millan.

Armed associations and the role of weapons

The project has shed light on a rather under-researched phenomenon. It has successfully questioned the correlation between armed groups, on the one hand, and the lack of democratisation, the authoritarian and fascist regimes of the post-WWI period or the absence of legitimated and effective state institutions, on the other. “Conversely, it has shown that people could lawfully gather in arms also in a period and in countries marked by the rule of law, ever-increasing political and social rights, and the broadening of popular participation,” reports Millan. What’s more, the project has shed light on long-term learning processes of contamination, adaptation and imitation between pre- and post-First World War armed groups, especially in Western Europe, and investigated the multiple meanings that violence acquired in pre-1914 armed associations. PREWArAs has also outlined the cultural and social backgrounds and fantasies of armed associations’ members, from their sense of order and social peace to their ideals of manliness and physical prowess. “On a final note, the project has demonstrated that weapons were daily objects in pre-1914 Europe and an integral part of the social and personal life of thousands and thousands of people,” says Millan.

Keywords

PREWArAs, armed associations, Belle Époque, pre-1914 Europe, organised political violence, weapons