Creature alive and kicking sans oxygen

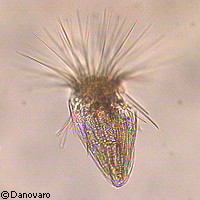

Can animals live without oxygen? New EU-funded research has found they can. Scientists recently discovered the planet's first multicellular organisms capable of surviving and reproducing in a 100% oxygen-free environment. Presented in the journal BioMed Central (BMC) Biology, the results are part of the EU-funded HERMES and HERMIONE projects, which received EUR 15.56 million and EUR 8 million under the Sixth and Seventh Framework Programmes (FP6 and FP7) respectively. The creatures, found deep on the floor of the Mediterranean Sea, subsist in an environment that has no oxygen but is rich in toxic sulphides. The scientists said the multicellular organisms, which are members of the Loricifera group, are not only alive, but metabolically active and even capable of reproducing. The team discovered the organisms in the course of 3 oceanographic expeditions carried out over a 10-year period. The researchers were looking for living fauna in the sediment of the Mediterranean's L'Atalante basin, which is around 200 kilometres off the western coast off the Greek island of Crete. This deep-sea hypersaline basin, which is about 3.5 km deep, is for the most part completely anoxic (an absence or severe deficiency of oxygen). 'These extreme environments have been thought to be exclusively inhabited by viruses, bacteria and archaea (i.e. single-celled microorganisms),' explained lead author Professor Roberto Danovaro, Director of the Department of Marine Science at the Polytechnic University of Marche in Ancona, Italy. 'The bodies of multicellular animals have previously been discovered, but were thought to have sunk there from upper, oxygenated, waters. Our results indicate that the animals we recovered were alive. Some, in fact, also contained eggs.' Using electron microscopy, the researchers found that these tiny creatures possess organelles resembling hydrogenosomes, which are found in single-celled organisms living in anaerobic environments. Commenting on the results of this groundbreaking study, Professor Lisa Levin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in the US said: 'The finding by Danovaro et al. offers the tantalising promise of metazoan life in other anoxic settings, for example in the subsurface ocean beneath hydrothermal vents or subduction zones or in other anoxic basins.' For their part, Drs Marek Mentel and William Martin, respectively from Comenius University in Slovakia and Dusseldorf University in Germany, noted: 'The discovery of metazoan life in a permanently anoxic and sulphidic environment provides a glimpse of what a good part of Earth's past ecology might have been like in 'Canfield ocean' [a sulphidic, partially oxic ocean existing between the Achaean and Ediacaran periods] before the rise of deep marine oxygen levels and the appearance of the first large animals in the fossil record roughly 550-600 million years ago.' Coordinated by the UK's National Oceanography Centre Southampton, HERMES ('Hotspot ecosystem research on the margins of European seas') targeted the forecasting of biodiversity change in relation to natural and man-made environmental changes by creating the first comprehensive pan-European margin Geographic Information System. The HERMES consortium comprised 50 partners including 9 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) from 17 European countries including Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Norway, Romania, Russia and Ukraine. HERMES ran from 2005 to 2009. HERMIONE (Hotspot ecosystem research and man's impact on European seas'), the successor to the HERMES project, seeks to advance our knowledge of the functioning of deep-sea ecosystems and their contribution to the production of goods and services. Launched in 2009 and scheduled to end in 2012, HERMIONE is coordinated by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) in the UK and brings together 38 partners from across Europe.

Countries

Italy