Cell division caught on film

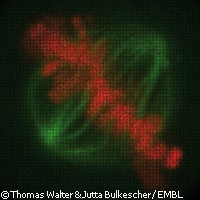

EU-funded scientists have recorded almost 200,000 films that reveal the human genes involved in a range of functions including one of the most fundamental processes of life: cell division. Details of their groundbreaking work are published in Nature. The MITOCHECK ('Regulation of mitosis by phosphorylation - a combined functional genomics, proteomics and chemical biology approach') project was funded to the tune of EUR 8.58 million by the 'Life sciences, genomics and biotechnology for health' Thematic area of the Sixth Framework Programme (FP6). The footage recorded by partners of the 10-member consortium, which includes the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Germany, has allowed the scientists to identify the hundreds of genes involved in mitosis (the most common form of cell division in humans). 'Without mitosis, nothing happens in life, really,' explained EMBL's Dr Jan Ellenberg, 'and when mitosis goes wrong, you get defects like cancer.' To discover which of the 22,000 genes in each human cell are specifically linked to mitosis, the team used RNA (ribonucleic acid) interference to 'silence' (or inactivate) each of the genes and place them 1 by 1 in a different set of cells. They then filmed these cells under a microscope over a 48-hour period, generating tens of thousands of time-lapse films detailing mitosis in action. This immense volume of footage was processed through a new computer programme specially created for the project. As a result, the scientists determined that almost 600 of our 22,000 genes have a role to play in mitosis. The next step for the team will be to study how these 600 genes act at the molecular level. Under the follow-up MITOSYS project, which is funded under the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7), the researchers will also investigate how these genes act in both healthy cells and certain cancers. The research might eventually identify markers that could help with diagnosis and lead to better treatment decisions. The MITOCHECK consortium has made all of the footage and analysis data involved in their current study freely available online, and will continue to do so in subsequent work. 'The end result is that we now have a very rich resource for the scientific community,' said Dr Ellenberg. 'Scientists can go to the website, type in the name of their favourite gene, and watch what happens when it is silenced; they can find out what other genes have similar effects - all in a few mouse clicks, instead of months or years of work in the lab!' The new gene silencing methodology created under the project has already been used several times since by the scientific community. 'A year after we developed these new siRNA microarrays, they're already in use by over 10 research groups from across Europe,' explained EMBL's Dr Rainer Pepperkok. Findings from a parallel study conducted by the same team into the proteins encoded by the 600 genes are also published in Science.

Countries

Germany