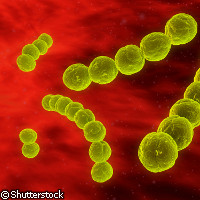

How bacterial interaction causes infection

An EU-funded team of researchers has identified a new array of genes that may be responsible for infections caused by pathogenic microorganisms, such as Group A Streptococcus, which causes thousands of deaths every year. The study, carried out as part of the EUR 3 million project PATHOGENOMICS, funded under the Sixth Framework Programme (FP6), will help scientists gain a better understanding of how bacterial-host interactions cause streptococcal infections. The results are published in the journal PLoS (Public Library of Science) Pathogens. The increase in infections caused by pathogenic microorganisms is being fuelled by both increasing resistance to anti-infective drugs and by global tourism and migration. One of these microorganisms is the human pathogenic bacterium Group A Streptococcus (GAS) which is carried by human beings in the upper respiratory tract. Usually the bacteria are inactive, but sometimes they cause a variety of illnesses: from minor skin and throat infections such as impetigo and strep throat, to major invasive ones such as toxic shock syndrome or necrotising fasciitis - widely publicised in the media in recent years as the 'flesh-eating disease'. The serious conditions of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease are also caused by the same bacterium and are responsible for an estimated 500,000 deaths a year. PATHOGENOMICS ('Trans-European cooperation and coordination of genome sequencing and functional genomics of human-pathogenic microorganisms') aims to bring together research programmes in different countries to fund and coordinate genome-based research projects. Currently, little is known about why the GAS bacterium may suddenly convert to a pathogenic condition. The bacteria usually exist as a 'community', not as single microorganisms, and therefore the communication systems between the bacteria are of key significance in determining their interaction with the host. Most communication between bacterial cells is achieved by signalling molecules that are secreted and 'sensed' by the bacteria. If the level of signalling molecules is high enough, it can activate the expression of genes that can coordinate the behaviour of the bacterial cells. But this activation only takes place if there are sufficient numbers of bacteria present (a process called 'quorum-sensing'). The study, led by Professor Emanuel Hanski from the Medical School at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, identified a new array of genes in the GAS bacterium and in a related strain, Group G Streptococcus (GGS). These genes are activated by a quorum-sensing peptide called SilCR. SilCR does not function in highly invasive strains of GAS, which suggests that the newly discovered genes may be involved in colonisation and establishment of commensal host-bacteria relationships. The research results also show that GAS and GGS strains can 'sense' their respective SilCR molecules, which means they can coordinate their pathogenicity and create a novel communication system between them. 'This study opens up exciting possibilities for controlling the pathogenicity of streptococcus A, which can cause several invasive life-threatening illnesses,' said Dr Marion Karrasch-Bott of German research institute Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, coordinator of the PATHOGENOMICS project. She added: 'The researchers not only identified a new genetic element that controls bacterial virulence, but also an array of genes regulated by this element. This will help in our understanding of how bacterial-host interactions can lead to mutual existence in some cases or to violent infections in other cases, and will eventually lead to innovative drugs that could prevent the bacteria from making the wrong decision.'