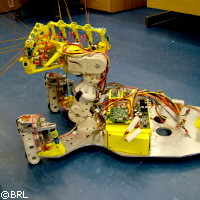

SCRATCHBOT could save lives

A British team of researchers has designed a robot capable of reproducing the behaviour of rats by using whiskers to explore its environment. The SCRATCHBOT ('Spatial cognition and representation through active touch') project - an innovative initiative by Bristol Robotics Laboratory and the University of Sheffield in the UK - is part of the EU-funded ICEA ('Integrating cognition, emotion and autonomy') project, which received over EUR 6 million under the Sixth Framework Programme's 'Information society technologies' Thematic area. ICEA, which will end in December 2009, is targeting the development of biologically inspired artificial intelligence systems. SCRATCHBOT's innovative features recently led to it being featured in the list of 'Best of What's New', published by the Popular Science magazine. Using 18 plastic whiskers in a sweeping back-and-forth (5 times per second) motion to navigate its surroundings, the SCRATCHBOT is a robot rat developed by the BRL, which is a partnership between the University of the West of England, Bristol, the University of Bristol, and the Active Touch Laboratory at the University of Sheffield. 'For a long time, vision has been the main biological sense most studied by scientists,' explained Dr Tony Pipe of the Bristol Robotics Laboratory (BRL). 'But active touch sensing is a key focus for those of us looking at biological systems which have implications for robotics research. Sensory systems such as rats' whiskers have particular advantages,' he added. 'In humans, where sensors are at the fingertips, they are more vulnerable to damage and injury than whiskers. Rats have the ability to operate with damaged whiskers, and broken whiskers on robots could be easily replaced, without affecting the whole robot and its expensive engineering. This award is a welcome recognition that our research is a leap forward for technology in this area.' The capacity in which animals use touch is what inspired the researchers to develop this new technology. Rats, for example, can determine the exact position, shape and texture of objects thanks to their whiskers. They can also make fast and accurate decisions about objects, and then use the information to develop environmental maps. When one of SCRATCHBOT's whiskers is bent as a result of contact with an object, a sensor on its shaft signals software to turn the robot toward the object. Whiskers in close proximity to an object move less, while whiskers that are further away make wider sweeping motions to determine the edges of the object. 'We held a workshop earlier this year at the University of Sheffield in which we were able to demonstrate the unique properties of the SCRATCHBOT and the direction of our research in the development of actively-controlled, whisker-like sensors for intelligent machines,' said Professor Tony Prescott of the University of Sheffield. 'Although touch sensors are already employed in robots, the use of touch as a principal modality has been overlooked until now. By developing these biomimetic robots, we are not just designing novel touch-sensing devices, but also making a real contribution to understanding the biology of tactile sensing.' The new technology can be of benefit to people in precarious situations like workers in collapsed mines. 'Whisker technology could be used to sense objects and manoeuvre in a difficult environment,' Dr Pipe commented. 'In a smoke-filled room for example, a robot like this could help with a rescue operation by locating survivors of a fire.'