How three-legged dogs improve robot design

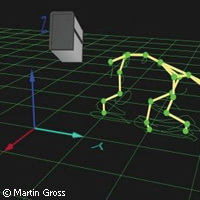

EU scientists working at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena in Germany have examined how three-legged dogs move in order to develop robots that can help them continue functioning in the event of the loss of a limb. EU support for the research came from the LOCOMORPH ('Robust robot locomotion and movements through morphology and morphosis') project, which received EUR 2.7 million from the 'Embodied intelligence' Initiative within the 'Information and communication technologies' (ICT) Thematic area of the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7). Canines are known for their resilience in the face of limb-loss, often managing to move about admirably on three legs. So researchers in Germany wanted to discover how they managed to move so capably without a full set of limbs. They looked at walking and running techniques in dogs with fore-limb or hind-limb amputations and found that the animals adopted different coping techniques or 'compensation strategies' to retain their mobility depending on which limb was missing. 'Natural terrestrial locomotion is designed for an even number of limbs,' explained Martin Gross, lead researcher and biologist at the Friedrich-Schiller University of Jena. 'After limb loss, for example by an injury, a re-organisation of the locomotive system is required.' Dr Gross and colleagues discovered that the dogs found it more difficult to deal with a missing fore-limb than a missing hind-limb. They explained that with a hind-leg amputation, the fore-limbs continued to act as they would normally in a four-legged dog, showing little or no compensation strategy. However, if a fore-limb was missing, the remaining limbs were forced to undergo careful adaptation to coordinate with each other via a process known as 'gait compensation', concluded the researchers. They suggested that this difference was due to the higher loading of the fore-limbs in comparison to the hind-limbs because of the distribution of the dogs' body weight. The scientists came to these conclusions after analysing dogs with fore-limb and hind-limb amputations running on a treadmill, synchronised to 10 high-speed infrared cameras, for 2 minutes at a time. They placed reflective markers on the dogs' skin to follow the movement of separate parts of the body and recorded the trajectory of the movements. They then made complex comparisons of the characteristics of movement, known as kinematics, between dogs with different limbs missing and also with the 'normal' movement of four-legged dogs. The results of this study were presented at the Society for Experimental Biology Annual Meeting in Prague in the Czech Republic on 1 July 2010. But the scientists insisted that their research was ongoing and said they hoped to make further measurements to consolidate their findings. Their work is an outcome of the four-year EU LOCOMORPH project being carried out by biologists, physicists and engineers at a host of institutions, notably the University of Zurich and the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale of Lausanne in Switzerland, the University of Syddansk in Denmark, the University of Antwerp in Belgium and the University of Ryerson in Canada, as well as the University of Jena. Kick-started in 2009, the project's goal is to advance robotic locomotion and movement through a multidisciplinary approach that takes into account biology, biomechanics, neuroscience, robotics and embodied intelligence. Researchers hope to find ways of increasing the efficiency, robustness, and thus the usability of robots in unknown environments. Future work under the LOCOMORPH project to develop a better understanding of locomotive activity will examine voluntary and involuntary changes to body movement in a wide range of different animals, from lizards to okapis, and baboons to humans.

Countries

Germany