New technologies could end stem cell controversy

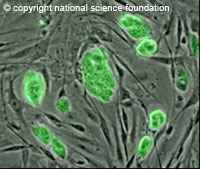

Stem cell research is considered by some to be the key to future developments in medical science, but by others it is a morally bankrupt avenue for research. If new technologies are successful in generating stem cells from adult cells, then research could take off, by side-stepping many of the moral objections to studying these special cells, and providing an ever more ready supply of stem cells for research. Two new articles, one written by a team from Edinburgh University and a second by a team from Princeton University in the US - both renowned as leaders in the field of stem cell research, have been published in the journal Nature. Both address this topic. The articles provide the strongest clues yet that this 'reprogramming' may indeed be possible. Stem cells are important to researchers for two reasons - their ability to divide again and again, and their ability to differentiate into different cell types. Currently, stem cells are 'harvested' from umbilical cord blood and, more controversially, from aborted foetuses. Stem cells can also be used from in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatments, when there is a surplus of cells. Under the Sixth Framework Programme (FP6), while priority was given to research on adult stem cells, namely those derived from derived from adults or umbilical cord blood, funding for embryonic stem cell research was explicitly excluded. In November 2005, ministers from Austria, Germany, Italy, Malta, Poland, and Slovakia signed a Vatican-led petition to ban embryonic stem cell research, although Italy removed its name following the fall of the Berlusconi government. Embryonic stem cell was also the key sticking-point in the recent debate on the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) at the European Parliament. Many MEPs vigorously objected to the use of stem cells in research, and the decision to maintain stem cell research passed by only 25 votes. Researchers are looking to develop a recipe for successful reprogramming of ordinary, differentiated cells, turning them into stem cells. The technology is not yet available, but this new research suggests that the technology is not a long way off. 'Until a couple of years ago I thought the idea of reprogramming was ridiculous because we had no scientific idea of how to achieve it,' said stem cell biologist Austin Smith from Edinburgh University - one of the co-authors from the Edinburgh team - in an interview with Nature. Reprogramming technology was first seen in the creation of Dolly the sheep, revealed to the world in 1997. The procedures used to 'make' Dolly had relied upon reprogramming technology. However, this technology is more complex for human stem cells. One protein found to be key is known as Nanog. Nanog activates in growing embryos and controls other genes. The team created mouse embryonic stem cells that produce four times the Nanog, and when fused with a mouse nerve cells, the resulting cells could be transformed into stem cells very efficiently - up to 200 times more efficiently. But this is not the whole story. Researchers believe that the Nanog protein is just the beginning and that other proteins will be implicated. The second article, written by researchers in Princeton, identifies some of the candidate proteins. When these can be effectively screened for their effects in the creation of stem cells from differentiated cells, then the reprogramming technology will be a step closer, moving stem cell research ever further forward.

Countries

United Kingdom, United States