Neural and behavioural evidence that adolescents strategically use social information

Adolescence is a time of healthy ‘separation’ from parents in preparation for adulthood. It is accompanied by increasing reliance on peers for information. The outsized role of peer influence in decision-making has long been a topic of research. The exponential rise in social media use further amplifies the need to understand the way adolescents obtain, filter and use information. Most studies have relied on longitudinal observation or artificial laboratory experiments. The pioneering ERC-funded Social Smart project (website in Dutch) designed a ‘mobile lab’ – a van equipped with the technology to run Social Smart’s social psychology tests. It brought cutting-edge behavioural experiments to schools, capturing how influence spreads in real social networks of peers. Neural imaging and computational modelling complemented these studies.

Simple in-person tool and computational models

Wouter van den Bos of the University of Amsterdam, Social Smart coordinator, explains: “The Berlin Estimate AdjuStment Task (BEAST) task asks participants to make perceptual judgments such as estimating the number of objects in an image. They can choose to update their judgements based on social feedback, allowing us to measure how people weigh their own knowledge against social information.” The COVID-19 disruption, which occurred as the project began, made collecting data in schools impossible for some time. Serendipitously, it spurred the team to adapt and apply their computational models to real social media data such as Instagram posts and engagement metrics. This provided an unexpected opportunity to enrich Social Smart outcomes and insights.

Selective peer influence via strategic social information gathering

“Traditional studies have often portrayed adolescents as passive receivers of social influence. Our research shows that adolescents actively seek information and strategically choose whom to trust based on expertise, popularity and personal relationships,” underscores van den Bos. Furthermore, adolescents were more likely to rely on social information when lacking confidence in their knowledge but also considered the certainty/knowledge of the source. Analyses of online social media data enabled the first direct computational comparison of social media engagement between teenagers and adults. Computational, experimental and neuroimaging results pointed to ways adolescents differ from adults in susceptibility to social influence. “The brain changes during adolescence make young people more sensitive to social rewards such as ‘likes’ but also more capable of complex social learning,” explains van den Bos.

Implications for encouraging positive influence

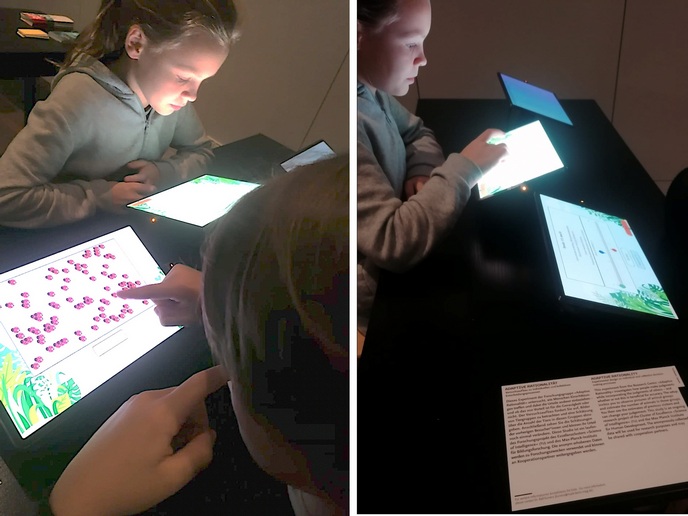

Given the project’s name, van den Bos was happy to see that adolescents were relatively ‘smart’ and strategic in finding and using social information. This will be increasingly important amid growing online engagement as well as mis- and disinformation. “We can help adolescents recognise trustworthy social sources by encouraging active inquiry and critical evaluation, potentially more effective than restrictive policies or warnings about peer pressure in decreasing negative influence and improving decision-making,” he says. Leveraging influential students and online ‘influencers’ to promote positive behaviours like good study habits and prosocial actions can play a role as well. Versions of the BEAST task have already been used in: the mobile lab, neuroimaging studies, citizen science projects in museums in Germany, the Netherlands and Japan, and the German Socio-Economic Panel, which is a large, long-running household survey. “We expect many more studies using our simple protocol in the future, enabling us to compare how social influence shapes decision-making across ages and cultures in real social networks,” van den Bos concludes.

Keywords

Social Smart, adolescents, social information, social media, decision-making, social influence, social networks, computational models, neuroimaging, peer influence