New insights into the role of medieval Bachelor debates

At the start of each academic year in the 14th and 15th centuries, Bachelor students had to participate in debates with the other Bachelors and their associates in a competitive evaluation procedure. These public performances, which took place in all European medieval universities, were called ‘Principia’ in Latin. This translates as ‘Beginnings’, an appropriate title, as they were an initiation to lecturing in the path of obtaining the title of doctor. “In these Principia the bachelors were expected to confront their peers (socii), demonstrating their rhetorical skills in the defence of controversial theses and refuting those of their colleagues. They had to display their intellect in devising arguments, their knowledge of authorities, and their witty capacity to entertain the public,” explains the DEBATE project’s principal investigator, Monica Brinzei, a research director at the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). As the choice of an interesting topic to debate was also a sign of academic creativity, the variety of topics was exciting. For example: Is God capable of creating a better world? Should anyone choose to live for 100 hours of intense pleasure rather than endure 10 years of excruciating pain? The team, with support from the European Research Council, set about identifying new manuscripts, editing the texts, establishing authorship for anonymous fragments and proposing an interpretation to explain how innovation was a key target in medieval academia. Fortunately, there was a technical shift at the time, equivalent to the move to open access publishing in academia today: a move from expensive parchment to more accessible paper. The use of paper gives rise to an increasing number of notebooks containing ideas for exams and theses. A treasure trove for the curious researcher.

Rendering medieval notes accessible for modern interpretation

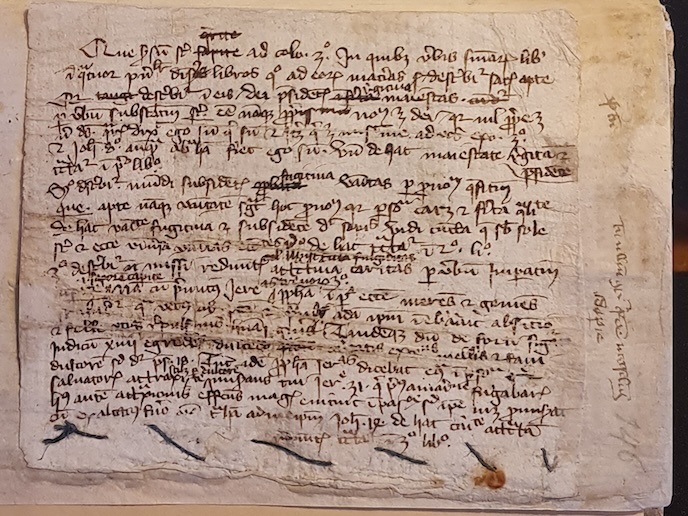

Accessing such notebooks is not a problem: the universities of Bologna, Cologne, Krakow, Paris and Prague all had a rich tradition of Principia debates. But unravelling the contents is a very different story. “We have to master first Latin and then Latin palaeography, which is the art of deciphering different letter shapes and abbreviations in unpunctuated medieval manuscripts. Medieval scribes of academic texts wrote almost every Latin word in an abbreviated form, a bit like an extremely cryptic SMS today,” Brinzei notes. It can take years to decode an entire thesis, as researchers need to learn both the general abbreviations employed in many genres of writing, along with the technical vocabulary and abbreviations specific to certain genres and even single doctrinal contexts. DEBATE also considered the codicology, or the art of analysing the materiality of a book, to tell us the story of when, why, how and, sometimes, by whom a text was copied. “In the text of principial debates, codicology mainly helps us to date a manuscript and, together with palaeography, also to discern if we are dealing with an autograph of one of the participants in the debate, or again to determine whether a manuscript was copied in Oxford, circulated in Paris and ended up in Vienna,” says Brinzei.

Identifying unknown medieval authors

Principia debates involved anywhere from two to over a dozen scholars, depending on the time, place and choices of the authors reporting the debates. Since the manuscripts record the dialogue between these authors, the team were able to attribute ideas and sometimes entire passages verbatim to previously unknown authors. Brinzei is convinced that the project succeeded in uncovering and clearly delineating the characteristics of this philosophical genre of oral performance and of the medieval textual heritage. Intriguingly, within these previously neglected texts, the DEBATE team traced many actions present in modern academic to these medieval Principia. The process of evaluation by peer reviewers, the pleasure and emotion of public performance in presenting research results, academic jealousy, persistence and sometimes obstinance in defending ideas, and the joy of thanking the people and institutions whose support led to success – all have their origins in these debates. “I was pleased to be in a position to provide the scholarly community, both those interested in the institutional context and those focusing on the ideas, with a detailed toolkit to identify new specimens in the future and to interpret correctly both those and the ones that are already known,” Brinzei adds.

Keywords

DEBATE, medieval notes, medieval authors, Principia, scholars, scholarly community, academic creativity, medieval scribes