Solving the mystery of horse domestication

One could make the argument that the history of civilisation happened on horseback. “Horses have revolutionised the circulation of ideas, people, languages, religions, conflict, and communication,” says Ludovic Orlando, director of the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse. But where did the domestic horse come from? “Over the course of some 5 000 plus years, we were able to transform the natural evolutionary trajectory of wild horses into more than 600 breeds of domestic horses,” adds Orlando. “The question is how did we do this?” With the support of the EU-funded PEGASUS project, Orlando led an effort to solve the mystery of horse domestication.

Conducting ancient DNA research

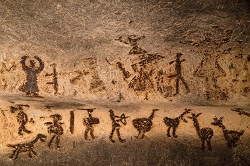

The project, which received support from the European Research Council, stands out in its use of innovative new technologies at the forefront of ancient DNA research. This included analysing DNA methylation in ancient remains and conducting a genetic characterisation of extensive horse remains spread across Eurasia and spanning many thousands of years. “We teamed up with the right archaeologists in each and every relevant country and managed to develop mutually beneficial relationships, which facilitated access to material that ultimately turned out to be key,” remarks Orlando. According to Orlando, the project was extremely lucky to have made several major discoveries. “Using this technology, we not only mapped out the homeland of domestic horse breeds, but also uncovered how breeding practices and migration patterns evolved over the past 4 000 years,” he explains. As to the former, researchers discovered that 5 000 years ago, many horse lineages roamed Eurasia, one of which was domesticated on the steppes of Central Asia. This original domesticated horse was soon replaced by a second, which was domesticated around 4 200 years in the western Eurasian steppes. “This horse spread like everywhere, eventually replacing almost all wild horse lineages – even those that were once depicted on cave walls by prehistoric artists,” remarks Orlando.

Changes in breeding practices

With the invention of spoke-wheel chariots, the domestic horse appeared further and further afield, and, as it did, breeding practices began to change. For example, during the past 2 500 years, breeders began to use selection to improve the horse in terms of size and strength. However, in the last few centuries, these changes in breeding practices resulted in a significant drop in horse genetic resources. “Our work helps fill in these gaps,” says Orlando. “By advancing the genomic resources for horses, we created the largest genome reference panels for both ancient horses and donkeys.” The project also developed new techniques based on patterns of DNA methylation to estimate the age-at-death and characterise such breeding practices as castration.

Global collaboration

PEGASUS’ success is the direct result of the over 100 people, including indigenous peoples, from around the world who collaborated on the project. “The horse has always helped bring people together, even if people don’t speak the same language or share the same culture,” he concludes. “This project gave me an opportunity to experience this first hand.” Orlando plans to continue his research through the Horse Power project. This ERC Synergy grant funded project will focus on the role horses played in the rise of the first steppe empire and the first imperial dynasty in China.

Keywords

PEGASUS, horses, wild horses, domestic horses, ancient DNA, DNA methylation, archaeologists, Horse Power