Tumour-on-a-chip innovation boosts cancer research

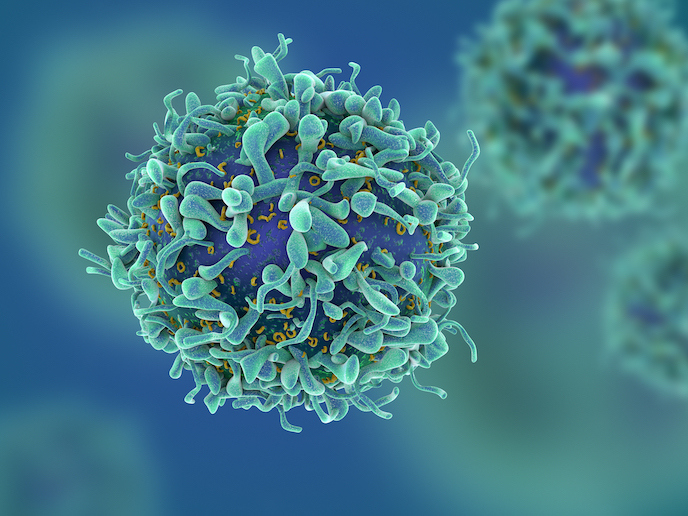

Breast cancer is still one of the most common cancers in women worldwide. While increased awareness and better treatments have led to a decrease in death rates in older women, the death rate in women younger than 50 remains unchanged. “The major cause of death is metastasis,” explains MTOAC project team partner Christa Ivanova, research and innovation manager at ELVESYS, France. “This is when cells break away from the primary tumour mass and invade tissues and organs via the bloodstream. Once the cancer forms metastases, survival chances decrease drastically.” The MTOAC project, which was undertaken with the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions programme, was launched with the aim of better understanding this process of metastasis. To achieve this, the project team set out to build a microfluidic device capable of recreating the physiological environment of a tumour. The idea is that this will provide scientists with a simple and cost-effective means of culturing and analysing tumour cells. Key benefits include delivering results comparable to in vivo models, while being at the same time less costly, more ethically sound and easy to operate.

Mimicking tumour environment

The microfluidic device developed by the project team consists of a tiny microfluidic chip where cells can be grown, along with pumps that regulate the flow of nutrients to the cells (thus mimicking the body). The chip itself contains three chambers connected by tiny channels. “The idea was that seeding cells in each compartment would allow us to study cell growth and behaviour,” adds Ivanova. After building the microfluidic cell culture platform, the project team seeded it with cells, including commercially available breast cancer cells. The cells were embedded in a hydrogel consisting of collagen to help them adhere to the microfluidic chip. The cells were then left to proliferate and form 3D structures. After a number of days, these ‘tumour-on-a-chip’ systems were analysed to assess glucose uptake, hypoxia and interactions between different cell types. “We found that tumour-derived cells consume more glucose,” explains Ivanova. “This is logical, since they show faster growth. We also found that the centre of the 3D cell culture becomes necrotic due to hypoxia. This is common in tumours, since fast cell growth prohibits a continuous supply with fresh blood/oxygen. This is a state that often initiates metastasis.” The team also found that a co-culture of breast cancer cells and blood vessel cells led to a migration of the former towards the latter. “These three observations are all in accordance with published literature,” notes Ivanova. “This suggests that the 3D cell culture system we established is capable of mimicking the real tumour microenvironment.”

Standardised solution

The success of the project underlines the potential of microfluidic technology in helping scientists to better understand the biological mechanisms behind cancer. “The complexity of microfluidics has in the past been intimidating,” says Ivanova. “We hope that with this easy-to-use microfluidic system, more researchers will be able to benefit.” Indeed, the MTOAC project represents an important milestone on the path towards a standardised tumour-on-a-chip system, which could eventually replace animal models where possible. Standardisation is critical – while there are several tumour-on-a-chip systems available on the market, these tend to be limited to specific cell lines, and remain very expensive. “We will continue to work on this system in order to make it more accessible and better known in the research community,” adds Ivanova.

Keywords

MTOAC, cancerous tumours, microfluidic, breast, cancer, cell, hypoxia, bloodstream