Laying the foundations for effective drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection

As the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic rages, the vaccination programmes launched by governments around the globe are an important pillar of protection against the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. However, a mere 5 % of the global population has been vaccinated so far, which means there’s still a long way to go. There are also other concerns. How long does a vaccine’s protection last? Will current vaccines be effective against new variants? Scientists don’t yet know. While these vaccine-related unknowns are worrying, the landscape for effective drugs against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants is even more so. At present, there are no medications that have been proven to provide safe and effective treatment against the virus. Researchers from the University of Southern Denmark have now presented a chemical compound that may form the basis for the development of drugs that can guard against viral infection. Supported by the EU-funded ChemEpigen project, their study has been published in the journal ‘Chemical Communications’. “Our approach is based on mimicking Nature, and the idea is to prevent the virus from entering the body’s cells,” observed Associate Professor of Medicinal Chemistry Jasmin Mecinović in a news release posted on the ‘EurekAlert!’ website. “If the virus does not enter the cells, it cannot survive. Instead, the immune system destroys the viral particles, thus preventing an infection,” explained Dr Mecinović, who is one of the four study authors and ChemEpigen principal investigator.

Creating decoys

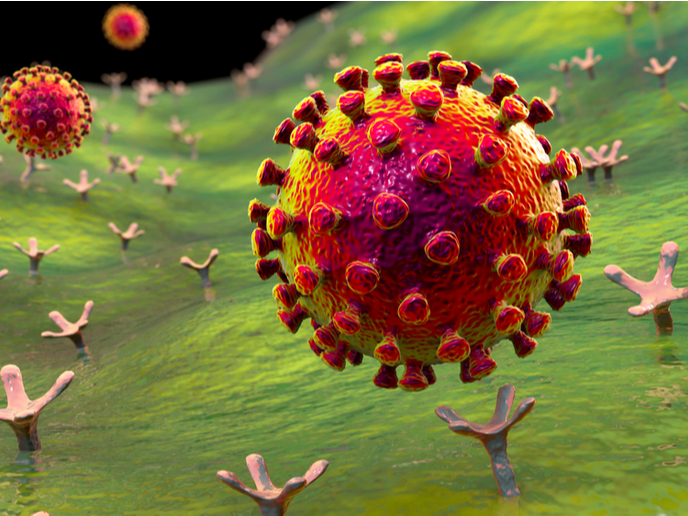

The SARS-CoV-2 virus can infect a person thanks to a distinctive protein called a spike protein that latches onto the host’s healthy cells. The spike protein binds to an enzyme on the host cell, allowing the virus to penetrate the cell and cause infection. The enzyme the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein specifically interacts with is called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). The ACE2 receptor is found on the surface of different cells located in the lungs, heart, kidneys, intestines and liver. According to the study, when peptides – short chains of amino acids linked by chemical bonds – are made to mimic the ACE2 receptor, they can act as decoys that stop the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein from binding to ACE2. “This suggests that molecular decoys based on the ACE2 receptor might be an effective therapeutic to prevent infection by the virus,” remarked first author Marijn Maas in the same news release. While this is only a small step in the journey to bring a new drug to market, it provides renewed hope for effective prevention of coronavirus infection. The next step, according to Dr Mecinović, “is to continue studying our synthetic peptide - for example by making variations of it to see if we can improve its potency.” The 5-year ChemEpigen (The chemical understanding of biomolecular recognition in epigenetics) project ends in March 2022. For more information, please see: ChemEpigen project

Keywords

ChemEpigen, COVID-19, coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, spike protein, ACE2, receptor