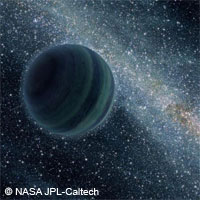

Ten previously undiscovered planets found floating in the Milky Way

Astronomers have discovered 10 new Jupiter-sized planets floating in interstellar space - far from the light of any nearby parent star. The discovery was made by an international team of EU-funded researchers conducting a planetary microlensing survey of the Milky Way galaxy. The study, carried out by astronomers from Chile, Japan, New Zealand, Poland, the United Kingdom and the United States, was funded in part by the OGLEIV (Optical gravitational lensing experiment: new frontiers in observational astronomy ') project, which received a European Research Council (ERC) Advanced Grant worth EUR 2.5 million under the 'Ideas' Thematic area of the EU's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7). Writing in the journal Nature, the team suggests that these lonesome planets were probably ejected from developing planetary systems. Although scientists had always had a hunch that free-floating planets existed, due to their distant location - 10,000 to 20,000 light-years away from Earth in the direction of the central bulge of the Milky Way - the planets had gone undetected until now. This discovery implies that there could be billions more free-floating Jupiter-style planets that can't be seen in the Milky Way galaxy alone; according to the team's estimates, there could be twice as many of them as there are stars and they could be just as common as planets that orbit stars. 'Our survey is like a population census,' said David Bennett, one of the study's authors from the University of Notre Dame in the United States. 'We sampled a portion of the galaxy, and based on these data, can estimate overall numbers in the galaxy.' The scientists were able to finally see these free-floating planets thanks to gravitational microlensing, which occurs when an object bends the light of a more distant star. According to Albert Einstein's theory of relativity, when large objects pass in front of a more distant star, the objects can act as a lens by bending and contorting the light of the star so that it appears brighter, thereby making it visible to astronomers on Earth. Over two years, the team analysed the central area of the Milky Way, or 'Galactic Bulge', and gathered data using the 1.8-metre-wide Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA) telescope in New Zealand, which scanned the stars at the centre of our Galaxy for gravitational microlensing events every hour. Without this special microlensing telescope, the research would have been impossible as this part of space is only visible using this technique. Although previous observations have uncovered more than 500 planets since 1995, these were mostly bound to host stars, and any free-floating mass objects found were usually masses over 3 times the size of Jupiter; scientists believe that these huge gaseous bodies form more like stars than planets. Named 'brown dwarfs', these star-like balls of gas grow from collapsing balls of gas and dust, but lack the mass to ignite their nuclear fuel and shine with starlight. Equally, scientists believe it is likely some planets are ejected from their early, turbulent solar systems due to gravitational encounters with other planets or stars. Without a host star to orbit, these planets would move through the Galaxy as our Sun and other stars do, in stable orbits around the Galaxy's centre. David Bennett explains how the discovery of 10 free-floating Jupiter-sized planets backs up this ejection theory: 'If free-floating planets formed like stars, then we would have expected to see only one or two of them in our survey instead of 10. Our results suggest that planetary systems often become unstable, with planets being kicked out from their places of birth.' This study is the fourth phase of the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) project - one of the largest scale sky-surveys worldwide, which has been on the go since 1992. So far, OGLE has contributed to many fields of modern astrophysics including gravitational microlensing, extrasolar planets searches, stellar astrophysics, and Galactic structure. The OGLE-IV survey also contributes to the search for Pluto-size dwarf planets from the Kuiper Belt, the search for free-floating black holes, and microlensing in the Magellanic Clouds and Galactic disk.For more information, please visit:Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw:http://www.fuw.edu.pl/astronomical-observatory.htmlNASA:http://www.nasa.gov/

Countries

Chile, Japan, New Zealand, Poland, United Kingdom, United States