Say hello to Inuk, Greenland's ancient Eskimo

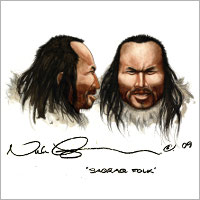

An international team led by the University of Copenhagen in Denmark has successfully decoded the genome of a man who lived on the western coast of Greenland around 4,000 years ago. Published in the journal Nature, the study's findings are part of the ECOGENE ('Unlocking the European Union convergence region potential in genetics') project, funded with EUR 1.09 million under the Regional programme of the EU's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7). Danish evolutionary biologist Eske Willerslev from the Centre for GeoGenetics, Natural History Museum of Denmark and the Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, along with PhD student Morten Rasmussen, led the team of 52 scientists that concluded a DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) analysis of ancient human hair found preserved in Greenland's permafrost. At first glance, the researchers believed the tuft of hair used for analysis belonged to a bear because it was so thick. Instead, they discovered that it belonged to a Palaeo-Eskimo whom they named 'Inuk', which means 'human' or 'man' in Greenlandic. Inuk hailed from the Saqqaq culture which was found in west and southeast Greenland from around 2,500 BC to 800 BC and was the first culture to settle in the New World Arctic. The detailed reconstruction of this ancient human genome joins the list of eight whole genomes of living people that have been decoded to date. So what did Inuk look like? The researchers point out that he likely had brown eyes, thick dark hair (although he was unfortunately prone to baldness) and type A positive blood. Inuk was dark-skinned and ate seal meat that he chewed with square, 'shovel-shaped' front teeth. Inuk was also genetically adapted to cold temperatures. The researchers say that although he lived in Greenland, Inuk is in fact more closely related to tribes in modern-day Siberia than to the Inuit (i.e. 'The People') that currently make their home in Greenland. The findings also help unlock the mystery of how Inuk's ancestors, known as the Chukchi people, migrated more than 2,000 kilometres from north-eastern Siberia to Greenland some 5,400 years ago. This migration wave, say the researchers, was independent of those of the ancestors of the Native Americans and Inuit. Professor Willerslev and his team made headlines in 2009 when they reconstructed the complete mitochondrial genomes of a woolly mammoth and an ancient human. The Danish scientist happened upon the hair tuft after a number of failed attempts to find early human remains in Greenland. 'I was speaking with the Director of the Natural History Museum in Denmark, Dr Morten Meldgaard, when we started discussing the early peopling of the Arctic,' Professor Willerslev explains. '[Dr] Meldgaard, who had participated in several excavations in Greenland, told me about a large tuft of hair which was found during an excavation in north-western Greenland in the 1980s and now stored at the National Museum in Denmark.' Once Professor Willerslev got the green light from the Greenland National Museum and Archives, he and his colleagues launched an analysis of the hair for DNA. After using a number of techniques, the team discovered that what they had in their hands was indeed human male hair. 'For several months, we were uncertain as to whether our efforts would be fruitful,' he goes on to say. 'However, through the hard work of a large international team, we finally managed to sequence the first complete genome of an extinct human. 'Our findings can be of significant help to archaeologists and others as they seek to determine what happened to people from extinct cultures.' Researchers from Australia, China, Denmark, Estonia, France, Greenland, Latvia, Russia, the UK and the US contributed to this groundbreaking study.

Countries

Australia, China, Denmark, Estonia, France, Latvia, Russia, United Kingdom, United States