Scientists prove Iron Age man died gruesome death

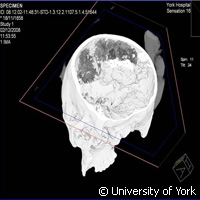

An analysis of an Iron Age skull that dates back 2,500 years has revealed that the man succumbed to a violent death, according to University of York researchers in the UK. Presented in the Journal of Archaeological Science, the research data suggest that the man, aged between 26 and 45, was hanged and then decapitated. The man's brain was buried separately and on its own. The York team first found the skull and brain remains in 2008, facedown in dark-brown organic-rich soft sandy clay. According to the archaeologists, who worked together with bio-archaeologists, neurologists and chemists, the man's brain is one of Europe's oldest surviving soft-tissue organs. The team sought to piece together the puzzle of how the brain could have survived when all the other soft tissues had decayed. They also reviewed details of the man's death and burial that could have played a role in safeguarding the vulnerable brain. The remains were found in one of several Iron Age pits at the Heslington East campus at York. Although both the skull and brain are being kept in strictly controlled conditions, the team used advanced tools like mass spectrometers and a computerised tomography (CT) scanner to examine some brain material samples. These samples, say the researchers, had a DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) sequence that matched sequences found only in some individuals from Tuscany in Italy, and from the Near East. They add that carbon dating placed the remains as far back as 673 BC to 482 BC. Tests also confirmed the presence of a range of lipids and brain-specific proteins in the remains. Commenting on the results, study leader Dr Sonia O'Connor of the University of Bradford and an Honorary Visiting Fellow at York says: 'It is rare to be able to suggest the cause of death for skeletonised human remains of archaeological origin. The preservation of the brain in otherwise skeletonised remains is even more astonishing but not unique. 'This is the most thorough investigation ever undertaken of a brain found in a buried skeleton and has allowed us to begin to really understand why brain can survive thousands of years after all the other soft tissues have decayed. 'The hydrated state of the brain and the lack of evidence for putrefaction [suggest] that burial, in the fine-grained, anoxic sediments of the pit, occurred very rapidly after death. This is a distinctive and unusual sequence of events, and could be taken as an explanation for the exceptional brain preservation.' The researchers are analysing how these lipids and proteins could have jointly formed the persistent material of the surviving brain, potentially shedding light on the circumstances between death, the burial environment and preservation of the brain.For more information, please visit: University of York:http://www.york.ac.uk/Journal of Archaeological Science:http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/622854/description#description

Countries

United Kingdom