Scientists tackle and trace infection prevention and control

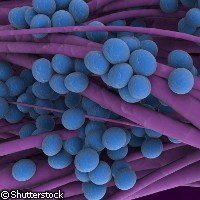

An international team of scientists has developed an innovative way to track the transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a single hospital setting. Presented in the journal Science, the findings demonstrate how this unique method can 'zoom' from large-scale inter-continental transmission events to the much finer detail of person-to-person infection of MRSA in just one hospital. The findings of this study will benefit researchers who are investigating how strains have the ability to spread quickly. They can also potentially fuel the creation and implementation of new infection control strategies - both for MRSA and other superbugs that are making their presence known. By using new very high-throughput DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) sequencing technologies, the researchers were able to compare individual MRSA isolates from patients to accurately show their genetic relatedness. The team rapidly identified single-letter changes in the genetic code as well as differences between the closely related MRSA isolates. 'We looked at two very different sets of samples,' said co-lead author Dr Simon Harris of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in the UK. 'We have 42 samples taken from people across the globe who became infected with MRSA between 1982 and 2003. The second set is from a single hospital in northeast Thailand, and consists of 20 samples from patients who developed MRSA infection within 7 months of each other, all possibly linked by a chain of person-to-person transmission. 'We wanted to test whether our method could successfully zoom in and out to allow us to track infection on a global scale - from continent to continent, and also on the smallest scale - from person to person.' Whole genomes of each sample were sequenced via next-generation DNA sequencing technology, according to the researchers. The use of this technique allowed the team to uncover the minutiae of single-letter genetic changes in the hospital samples. Based on the data, the researchers found that no two infections were triggered by completely identical bacteria. The team split the Thai hospital samples into two groups according to these subtle genetic differences. The researchers discovered 5 of 13 bacteria in 1 of the 2 groups were very similar and differed by only 14 single-letter changes. 'This group of five related MRSA strains caused infections in patients who were resident in intensive care units in adjacent blocks of the hospital, and all were isolated within a few weeks of each other,' co-lead author Dr Ed Feil from the Department of Biology and Biochemistry at the University of Bath in the UK pointed out. 'By contrast, bacteria from patients housed in other parts of the hospital were much less similar,' he added. 'This cemented our theory - based on the sequence comparison - that there were two different groups of isolates that had had been introduced to the hospital separately.' Based on their work, the researchers successfully determined the rate at which DNA sequences typically mutated. This finding offers researchers greater insight into the rate of evolution in vitro. According to the team, the MRSA strain they investigated acquired one single-letter change every six weeks. The researchers assessed samples from hospitals in North and South America, Asia, Australia and Europe. Comparison of whole genomes is what makes the new method successful, they said. 'This new method has allowed us to gain insights into fundamental processes of evolution in S. aureus, one of the most important bacterial pathogens in healthcare in the world,' said co-author Dr Sharon Peacock, from the Department of Medicine at the University of Cambridge and the Faculty of Tropical Medicine at Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. 'The implications for public health are clear: this technology represents the potential to trace transmission pathways of MRSA more definitively so that interventions or treatments can be targeted with precision and according to need.' Participating in this study were researchers from Portugal, Thailand, the UK and the US.