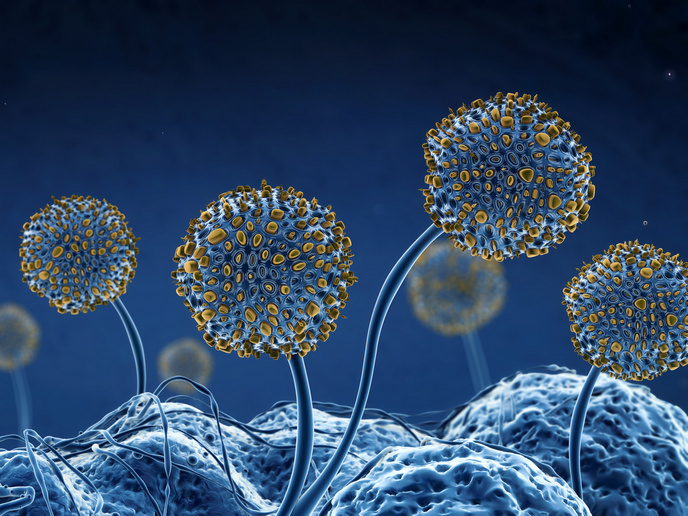

Mapping global fungi from air samples

A global study supported by the EU-funded LIFEPLAN and INTERACT projects used DNA sequencing to identify fungi from air samples collected worldwide. The study reveals groundbreaking information about how climatic and evolutionary factors affect the occurrence and seasonal variation of known and unknown fungi. “This knowledge is essential not only to understand where and when different fungal species thrive, but also to predict their fate under the ongoing global change,” states study lead author Dr Nerea Abrego of LIFEPLAN project coordinator University of Jyväskylä, Finland, in a news item posted on the university’s website. Scientists currently know only a tiny fraction of the species of our planet’s fungi. Obtaining more information on fungi could help scientists gain better insight into the environment and ways to preserve nature’s declining diversity.

Airborne treasure

It turns out that the key to mapping biodiversity was all around us, all along. “Air is a real treasure trove for nature research,” remarks Dr Abrego. “It is full of DNA from plants, fungi, bacteria, insects, mammals and other organisms.” The multidisciplinary research team focuses on the development of statistical modelling, bioinformatics and AI methods for using new types of biodiversity data for accurate forecasting. The scientists used airborne DNA from samples collected from 47 sites around the world to identify fungi. “There are more than [sic] million insect species in the samples already collected, which is many more species than have been described by science so far,” observes Prof. Otso Ovaskainen, also from the University of Jyväskylä. “The enormous size of the data set makes analysis challenging. We have more than a hundred years of sound, millions of camera trap images, and billions of DNA sequences.” Almost all fungi are at least partially spread through the air. For this reason, the researchers’ analysis was not limited to boletes and russulas, but also extended to other fungi such as lichens, bracket fungi, moulds and yeasts. “One particularly interesting subject for further research is a more detailed review of the sequences for fungi that are important to humans,” notes Dr Abrego. “These include fungal diseases of humans, crops and production animals, as well as fungi that indicate the progress of the loss of nature and the weakening of natural ecosystem processes.” Prof. Ovaskainen believes that this new way of sampling biodiversity outlined in the study supported by the LIFEPLAN (A Planetary Inventory of Life – a New Synthesis Built on Big Data Combined with Novel Statistical Methods) and INTERACT (International Network for Terrestrial Research and Monitoring in the Arctic) projects will revolutionise biomonitoring and biodiversity forecasts in the coming years. For more information, please see: LIFEPLAN project website INTERACT project website

Keywords

LIFEPLAN, INTERACT, fungus, air, biodiversity, DNA