Novel method finds helpful enzymes easier

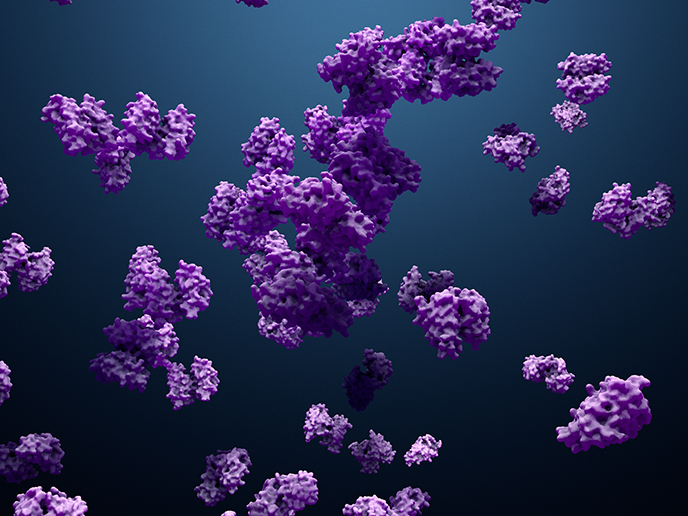

Enzymes are proteins found within cells that are commercially used to control and accelerate reactions in order to quickly and accurately obtain desired final products. From pharmaceuticals and biofuels to food and beverage and consumer goods, they are valuable because they make industrial processes economical, less toxic and more sustainable.

Search for industrially useful enzymes in nature

Enzymes are increasingly being discovered, but finding them is not easy. Discovering a new enzyme in natural surroundings first requires identifying a place where microbes that need such an enzyme might live. A research team partially supported by the EU-funded METAFLUIDICS and PicoCB projects have developed a new technique to break open cells that could assist in this pursuit. The results were published in the journal ‘ACS Synthetic Biology’. The method leaves several cells intact, and this enables them to be recovered and further examined. It is an important step in screening for beneficial enzymes. Enzymes are involved in each step of DNA replication. “It’s easy to collect DNA, it’s easy to clone them, and it’s easy to introduce them into these microorganisms,” explains corresponding author Rahmi Lale, a synthetic biologist at METAFLUIDICS project partner Norwegian University of Science and Technology, in a news item posted on the ‘Phys.org’ website. “But all of a sudden you have hundreds of millions of different cells. Every one of them carries something unique, but you don’t know which carry things that you are interested in.”

From screening to hole control

The researchers used microfluidics – the science of manipulating and controlling very small amounts of fluids – to screen the microbes 10 000 times faster than previous techniques. The microbes are confined to water droplets that rest in an oil-based carrier fluid. However, the cells have to be opened up to be tested because the majority of the potentially useful enzymes are made within those microbes. The system intentionally pierces a cell’s membrane, so the interior contents spill out into its surroundings. Then it can be tested for the existence of whatever type of enzyme the researchers are searching for. “We have a substrate that waits for the enzyme to come and interact with it,” notes Dr Lale. A positive match will trigger a reaction. Thanks to the new system, the team can purposefully leave some cells intact so they can be recovered afterwards. “Because we can control how many holes we’re introducing, we can also control how many cells die. We’re not killing them all, and that’s important.” Dr Lale elaborates: “If something of interest happens in one particular droplet, then we can recover that droplet. Thanks to cells growing so quickly, we can take the droplet, put it in a growth medium and the next day have a billion cells again. Then recovery of DNA becomes a really simple task.” The researchers are now working together with PicoCB project coordinator University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom to use the system for searching through environmental DNA samples from various locations. This could result in fascinating enzymes. METAFLUIDICS (Advanced toolbox for rapid and cost-effective functional metagenomic screening - microbiology meets microfluidics.) ended in November 2020. PicoCB (Exploring the Chemical Biology of Sequence Space via Picoliter Droplets) will be completed in September 2022. For more information, please see: METAFLUIDICS project website PicoCB project

Keywords

METAFLUIDICS, PicoCB, enzyme, industrial process, cell, microfluidics, microbe, droplet