Women migrants at the centre of thriving early modern Turin

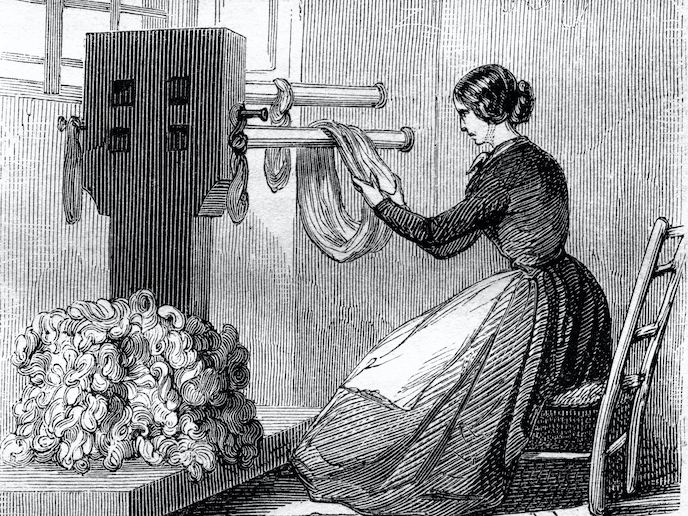

Women were central to migration to the burgeoning city of Turin, capital of the Duchy of Savoy in Italy, in the 18th and 19th centuries, EU-funded research at the University of Cambridge has shown. Their dowries often paid for the initial moving and settling costs. Married and unmarried women found jobs in the booming service, manufacturing and craft sectors, the study on the FemEcoMig project reveals. “My research shows women were not mere followers of male migrants, but proactive players,” says Beatrice Zucca Micheletto, research fellow supported by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie programme. “For a long time, scholarly literature tended to describe migrant women moving with their husbands, fathers or brothers as followers, who performed basic menial work as housewives or caregivers for their own household or for other family members.” But Zucca Micheletto gained a richer understanding of the role women played in Turin’s settlement by examining population censuses, court documents and notary deeds from 1705 to 1858. She drew on her participation in the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure. The evidence showed Turin attracted high rates of both female and male migration even before industrialisation led to the explosion of cities in the 19th century. “This high migration happened despite periods of social and economic crises, despite the war and the Napoleonic annexation,” Zucca Micheletto says. The research enriches historians’ understanding of female servants in the Turinese labour market. Hungarian-British economist John Hajnal and British historian Peter Laslett argued servanthood was a crucial feature of the Western European marriage pattern. Women married later in parts of Europe, starting in the 16th century. Teenage boys and girls began as servants and amassed money until quite an advanced age, with a view to future marriage. However, the FemEcoMig research showed female foreign servants in Turin spanned all ages and different life-cycle phases and were both married and unmarried. As well as working extensively in the service sector as servants, waitresses, chambermaids and governesses, female migrants also pushed into the craft and manufacturing sectors. They spun and wove silk, made laces, ribbons and trimmings, sewed and knitted from their homes and also worked in workshops and the first factories. Some were shoemakers and cobblers. In the 19th century an increasing number of them joined the tobacco industry. FemEcoMig also looked at the process of 500 migrants getting naturalised, becoming subjects of the Duke in the 18th century. Few foreigners became naturalised. Doing so did not confer the political or civil rights it does today, but it did come with economic advantages. They escaped the ban on foreigners transferring property to their offspring and could trade and work freely throughout the country. Zucca Micheletto hopes her work will encourage further interdisciplinary and historiographical approaches to better understand the history of migration and women’s role in it: “FemEcoMig unveils the crucial economic and social role of migrant women in independent migration as well as in family migration.”

Keywords

FemEcoMig, women migrants, early modern Turin, Savoy, Turinese labour market, migration