Sophisticated technology reveals potentially habitable exoplanet

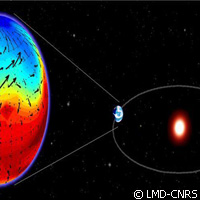

Scientists in France have succeeded in identifying the first potentially habitable exoplanet using a sophisticated computing model. Presented in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the Gliese 581d planet orbits a red dwarf star; its surface is covered in liquid water, its atmosphere is stable and its temperatures are comfortable. And it's only some 20 light years from Earth. The research was funded in part by the E3ARTHS ('Exoplanets and early earth atmospheric research: theories and simulations') project, which received a European Research Council grant worth EUR 720,000 under the EU's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7). Astrophysicists have been working on finding the first habitable planet for a number of years. Investigations for the most part have been carried out in the 'habitable zone' around stars, what experts define as the range of distances in which planets are not too hot or cold for life to exist. Curiosity about the red dwarf star Gliese was piqued three years ago when scientists from the United States said they had detected two planets orbiting seemingly close to the inner and outer edge of its habitable zone. Gliese 581d was the furthest away, and was thus deemed to be too cold for life to flourish. Fast-forward 3 years, and another team of scientists revealed their discovery of a new planet called Gliese 581g. They believed that this planet's mass was similar to Earth's and was situated near the centre of the habitable zone. But an independent evaluation later revealed that this was not the case. Some experts claim Gliese 581g does not exist, suggesting that it could just be the result of noise in 'ultra-fine measurements of stellar wobble' that are required to identify exoplanets in this system. At the end of the day, Gliese 581d appears to be a potentially habitable exoplanet. Robin Wordsworth and colleagues from the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique of the Institut Pierre Simon Laplace in France say Gliese 581d has a mass at least 7 times that of our planet, and is around twice its size. In order to determine if Gliese 581d is a good candidate, the team developed a computer model with the capacity to simulate possible exoplanet climates. This was particularly important because it was unclear whether the planet could withstand global glaciations and/or atmospheric collapse. They said the planet receives 35?% less stellar energy than Mars. But their three-dimensional climate simulations showed that Gliese 581d has surface liquid water and a stable atmosphere, 'making it the first confirmed super-Earth (exoplanet of 2-10 Earth masses) in the habitable zone'. Not only is the climate of the planet stable against collapse, but its comfortable temperatures can allow for the existence of oceans, clouds and rainfall. It should be noted that their simulations also revealed that the atmosphere efficiently redistributed daylight heating, thus keeping any atmospheric collapse on the right side or at the poles in check. The researchers say that based on the infrared radiation emitted by the model, they 'propose observational tests that will allow these cases to be distinguished from other possible scenarios in the future'. So researchers are enthusiastic about Gliese 581d being one of the closest galactic neighbours of Earth. And while more work needs to be done, scientists will obtain the tools they need to get the information they need for this potentially habitable planet. Experts from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the Université de Bordeaux in France contributed to this study.For more information, please visit: Institut Pierre Simon Laplace:http://www.ipsl.fr/en/The Astrophysical Journal:http://iopscience.iop.org/0004-637X

Countries

France