Fight against tropical parasitic diseases moves forward

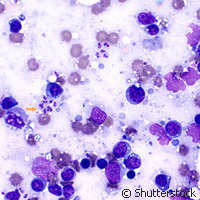

European researchers have discovered new compounds that may help fight a series of killer tropical parasitic diseases. Current drug treatments for diseases caused by trypanosomatid parasites such as African Sleeping Sickness, Chagas disease and Leishmaniasis are often inadequate due to drug toxicity and resistance, but new findings from the pan-European team from Belgium, Germany and Italy could move forward treatment development for these diseases. The study, published in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, identifies non-folate compounds as potential anti-parasitic agents that were discovered after the scientists applied a virtual screening approach to find out how different combinations of inhibiting enzymes affected the parasite's activity. To survive, trypanosomatid parasites require folates and the coenzyme biopterin, which are reduced by the enzymes dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and pteridine reductase (PTR1). When DHFR is inhibited, DNA replication is impaired, resulting in cell death. However in trypanosomatids, PTR1 is overexpressed when DHFR is inhibited, and PTR1 can take on the role of DHFR by reducing folates, thus ensuring parasite survival. Therefore, to treat parasitic diseases, both metabolic pathways must be blocked at the same time by inhibiting DHFR and PTR1 with a single drug or a combination of two specific inhibitors. As PTR1 is not present in humans it is an excellent target for the design of specific compounds that target the parasite. The team used a virtual screening approach combined with experimental screening methodologies in order to identify non-folate inhibitors of Leishmania PTR1. Optimisation was performed in two rounds of structure-based drug design cycles to improve specificity for PTR1 and selectivity against human DHFR, resulting in 18 drug-like molecules with low micromolar affinities and high in vitro specificity profiles. Assays of efficacy - the procedure in molecular biology for testing or measuring the activity of a drug or biochemical in an organism or organic sample - were carried out with cultured Leishmania cells and showed six compounds that were active in combination with a DHFR inhibitor. In addition, one of these compounds was also effective alone and several showed low toxicity profiles. One compound has also previously been approved for treating diseases of the central nervous system, and now there is the chance that it could also be used as an anti-parasitic drug. Leishmaniasis, African Sleeping Sickness and Chagas disease are just some of the infectious diseases currently affecting millions of people around the world, predominantly in developing countries. The World Health Organisation (WHO) reports that African Sleeping Sickness occurs in 36 sub-Saharan African countries where there are tsetse flies that can transmit the disease. In addition, it is rural populations that are most exposed to the fly and therefore most at risk. Leishmaniasis affects about 12 million people worldwide and, according to the WHO, the disease can have a wide range of clinical symptoms, which may be either cutaneous, mucocutaneous or visceral. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis is the most common form and visceral Leishmaniasis is the most severe form, in which vital organs of the body are affected. Diseases like Leishmaniasis are also often labelled 'neglected' diseases despite being responsible for an estimated 500,000 deaths and millions of disabilities each year. Biomedical research funds are often more focused on AIDS, Tuberculosis or Malaria. The challenge now is to shift this imbalance towards tackling tropical diseases too.For more information, please visit: Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies: http://www.h-its.org/english/index.php

Countries

Belgium, Germany, Italy