ESA's 'time machine' provides new glimpses into the past

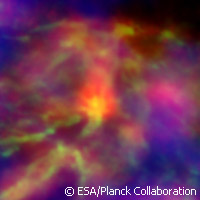

In the first data release from the European Space Agency (ESA) Planck mission on 11 January, thousands of never-before-seen dusty cocoons where stars are forming were revealed in unprecedented detail. Among the many results presented are yet other actors on the cosmic stage, like some of the most massive clusters of galaxies ever observed. 'These new results are all vital pieces of a jigsaw that could give us a full picture of the evolution of both our own cosmic backyard - the Milky Way galaxy that we live in - as well as the early history of the whole universe,' points out Dr David Parker, Director of Space Science and Exploration at the UK Space Agency. Planck was launched in May 2009 on a mission to detect light from just a few hundred thousand years after the 'big bang', an explosion at the dawn of the universe some 13.7 billion years ago. The spacecraft's state-of-the-art detectors survey the entire sky, measuring the cosmic microwave background, the rippling glow covering the whole sky that is a relic of the big bang. However, there are many other objects in the universe giving out light at the same wavelengths, including cold dust, hot gas and electrons swirling in magnetic fields. All these emissions are quietly being identified and removed so that Planck can achieve its ultimate goal of observing a mostly uncharted part of the electromagnetic spectrum. 'This is a great moment for Planck. Until now, everything has been about collecting data and showing off their potential. Now, at last, we can begin the discoveries,' says Jan Tauber, ESA project scientist for Planck. And indeed, from the closest neighbours of the Milky Way to the distant reaches of space and time, the all-sky Planck images represent an extraordinary treasure chest for astrophysicists. By observing the 'first light' after the 'big bang', they are able to distinguish between competing cosmological models. While hardly anyone today questions the broad outlines of the 'big bang' model (that the universe started as a very hot and dense fireball which gradually expanded and cooled), some uncertainties still remain. For instance, cosmologists are still puzzled about the nature dark matter, which could make up a substantial percentage of the matter in the universe. Drawn from Planck's continuing survey of the entire sky, the mission's catalogue contains massive clusters of galaxies, including a handful of newfound ones. The mission's science team focused on some of the most massive clusters - holding the equivalent of a million billion suns worth of mass - to learn more about how much matter it contains and how fast it is expanding. Furthermore, 'because Planck is observing the entire sky, it is giving us a comprehensive look at how all the smaller structures of the universe are connected to the whole,' explains Jim Bartlett with the Université Paris Diderot in France and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the US. Like the Cosmic Background Explorer and Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe before it, Planck is designed to pick up faint variations in the cosmic microwave background, which preserve some details of the earliest moments after the 'big bang'. Scientists believe that the variations occur because early fluctuations in the universe were expanded as the universe underwent inflation, but also provide indications of its present conditions. Dr Clive Dickinson with the University of Manchester in UK adds: 'We are now becoming rather confident that the anomalous emission is due to nano-scale spinning grains of dust, which rotate up to ten thousand million times per second. This is a great result made possible by the exceptional quality of the Planck data.' '[The first results from the Planck mission] are the tip of the scientific iceberg. Planck is exceeding expectations thanks to the dedication of everyone involved in the project,' says David Southwood, ESA Director of Science and Robotic Exploration. 'However, beyond those announced on [January 11], this catalogue contains the raw material for many more discoveries. Even then, we haven't got to the real treasure yet, the cosmic microwave background itself.'For more information, please visit: ESA:http://www.esa.int/esaCP/index.html ESA's Planck mission:http://www.esa.int/SPECIALS/Planck/index.htmlUK Space Agency: http://www.ukspaceagency.bis.gov.uk/default.aspx University of Manchester:http://www.manchester.ac.uk/ Jet Propulsion Laboratory:http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/