How approachable is Venus?

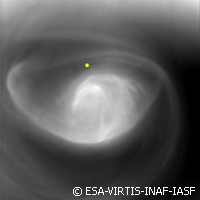

Latest updates from the Venus Express mission of the European Space Agency (ESA) reveal that the atmosphere high above the morning star's poles is 60% thinner than expected. A series of low passes has taken the spacecraft directly through the upper reaches of the planet's poisonous atmosphere. This experiment, unprecedented for Venus, has returned 10 measurements to date. The campaign began in July 2008 and has, so far, involved low passes in August 2008, October 2009, February 2010 and April 2010. It is expected to deliver crucial information on the density of the Venusian atmosphere, which extends from the surface up to an altitude of approximately 250 kilometres (km). The spacecraft currently circles Venus on a highly elliptical 24-hour orbit, a round trip that takes it down to an altitude of 250 km from the surface and back out to a distance of 66,000 km. During the remote part of the orbit, the Venus Express is affected by the gravity of the Sun, which pulls it slightly off course. Course adjustments are needed every 45 days or so, at which point the engines are fired to compensate. The fuel required for these course corrections will run out in 2015. Reliable density data would enable the mission controllers to assess the scope to move the spacecraft into a lower orbit. This would help to preserve precious fuel and further extend the lifetime of the mission, prolonging an adventure which has already outlasted initial expectations. However, says team member Dr Pascal Rosenblatt of the Royal Observatory of Belgium: 'It would be dangerous to send the spacecraft deep into the atmosphere before we understand the density.' The team is currently considering options to use the drag of the planet's atmosphere to place the Venus Express on a closer orbit. This change could halve the time needed to circle the planet and would also open up opportunities for further measurements. Establishing the new orbit would, however, involve some very intricate manoeuvering and could transform the spacecraft's easy relationship with Venus into a fatal attraction. 'The timetable is still open because a number of studies have yet to be completed,' says Dr Hakan Svedhem, ESA Project Scientist Venus Express. 'If our experiments show we can carry out these manoeuvres safely, then we may be able to lower the orbit in early 2012.' Whatever the decision, the ability to take these measurements is an achievement in its own right, as the craft's instrumentation was not designed to sample the atmosphere directly. Instead, density is calculated on the basis of deceleration, observed by radio tracking stations on Earth as the spacecraft dips into the atmosphere and is slowed down by the Venusian equivalent of air resistance. Extending the scope for observation, operators at ESA's European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany have also positioned the spacecraft's solar wings in a way that causes it to twist as it enters the atmosphere. To create the spin, one of the wings is placed face-on, while the other is turned edge-on. This particular feature has revealed considerable differences in atmospheric density between the day side and the night side of the planet. So far, Venus Express has managed to dive 75 km into the atmosphere, during a low pass in April 2010 which took it down to 175 km above the surface. An attempt at 165 km is scheduled during the week of 11 October. Beyond considerations about narrower orbits and extended lifetimes, these unexpected glimpses into an alien world have already delivered exciting new input. 'We couldn't see this region with our instruments because the atmosphere was too thin to register, but now we are sampling it directly,' says team leader Dr Ingo Mueller-Wodarg of Imperial College London in the UK. The mission scientists are currently investigating the reasons for the intriguing low density above the planet's poles, a phenomenon that may hint at unanticipated natural processes.

Countries

Belgium, Germany, United Kingdom