Scientists follow the voyages of marine microorganisms

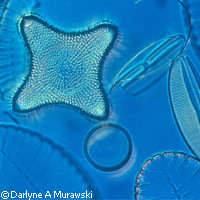

Two teams of scientists have taken a crucial step forward in understanding the distribution of planktonic microbes in our oceans. The studies, published in the journal Science, increase our understanding of marine biodiversity and show that neither diatoms (a group of microscopic algae) nor marine bacteria follow the same patterns as larger organisms. Supported by the EC's Marie Curie mobility scheme, Dr Pedro Cermeño of the University of Vigo in Spain studied the dispersal of diatoms to address a hypothesis that was first formulated more than 200 years ago: when it comes to microbial species, 'everything is everywhere, but the environment selects'. Dr Cermeño and his colleagues studied fossils of diatom assemblages that originated in far distant and contrasting open-ocean environments, and tested the importance of both environmental selection and dispersal limitation on the distribution of these 'morphospecies' in the world's oceans. In larger species, the spatial range of distribution spreads from the centre of origin. The farther away from this centre, the less individuals of the species will have in common. The fossil study showed that this does not seem to apply to diatoms; their dispersal is not limited in the same way as that of larger animals. For example, a marine setting prevents geographic isolation over long periods of time. 'Our results imply that the biodiversity and macroevolutionary patterns at the microbial level fundamentally differ from those of macroscopic animals and plants, negating the idea that all living things follow similar ecological and evolutionary rules,' the scientists conclude. This conclusion is corroborated by a second study, also published in Science, which describes the discovery of high numbers of heat-loving, anaerobic bacteria in the subzero sediments in the Arctic Ocean off the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen. Analysis of the distribution of these bacteria might help trace seepages of fluids from hot seafloor habitats, and could reveal currently unidentified offshore petroleum reservoirs. Together with an international team of scientists, lead investigator Dr Casey Hubert of the University of Calgary in Canada theorises that the bacteria found in the Arctic sediment may originate from a deep pressurised oil reservoir from which upward-leaking hydrocarbons carry bacteria into overlying seawater. The group's alternative hypothesis is that the bacteria might have been picked up at their original habitats in hydrothermal vents and hot spots by ocean currents to be deposited in the Arctic. 'The genetic similarities to bacteria from hot offshore oil reservoirs are striking,' says Dr Hubert. 'We expect ongoing surveys will pinpoint the source, or sources, of these misplaced microbes. This could have interesting applications if they are really coming up from leaky petroleum reservoirs.' Once removed from their hot and hostile habitat, heat-loving or thermophilic bacteria will start hibernating as spores in colder sediments. Those dormant forms, which can withstand adverse conditions for long periods of time, can be revived. 'The Arctic thermophiles could hold important clues for solving broader riddles of bio-geography,' says Dr Hubert.

Countries

Austria, Canada, Germany, Denmark, United States