New cells in the human heart a beat away

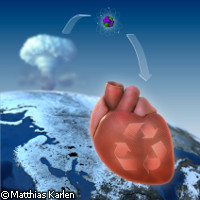

Researchers at Sweden's Karolinska Institute have answered the disputed biomedical question of whether the human heart generates new cells or is equipped from birth with a prescribed number that decreases over time, unreplenished. Their findings, funded in part by the EU and published in the journal Science, show that in the course of a human life, fewer than half of some heart cells (cardiomyocytes) are in fact replaced. Analysing this process further could prove immensely beneficial as a means to treat cells damaged by heart attacks and to redirect therapeutic strategies. Research into a precious organ like the human heart is no mean feat, explained Professor Jonas Frisén in a podcast interview with Science. There are several methods to study heart cell turnover in animals, but findings from such studies are not readily applicable to humans. The team came up with an alternative strategy: 'Instead of prospectively labelling cells, we are retrospectively determining the age of cells,' explained Professor Frisén. The novel approach, also used in archaeological dating, involved taking advantage of an unlikely opportunity: a geophysical event. Nuclear bomb tests conducted above ground during the Cold War between 1955 and 1963 resulted in the massive production of the radioactive isotope carbon-14. It was only a matter of time before the highly elevated levels of carbon-14 in the atmosphere were then mirrored in the cells of plants, animals, humans and other forms of life on Earth. Since the bans on this type of testing, the carbon-14 levels in our DNA have been dropping rather quickly, explained Professor Frisén. This drop is due to the uptake of 'biotopes' and diffusion, resulting in different atmospheric levels at different times. The researchers cleverly used the isotope to mark the date for cell rebirth. They carbon-dated the heart cells of people born both before and after the nuclear bomb testing to determine when DNA synthesis in these cells took place. According to the researchers: 'When a cell has been born in the human body at different times during the past decade, it will integrate carbon-14 in its genomic DNA at the level exactly corresponding to the atmospheric level. So by measuring carbon-14 in the DNA of cells we can read a date mark that is written into the DNA of cells and establish when they were generated. In this way, we can retrospectively say how old cells are, and infer how much turnover there must have been.' After around 4 years of study, Professor Frisén and his team have now established that cardiomyocytes, which make up around 20% of the cells in the human heart, renew each year at a rate of 1% from age 25. This gradually reduces to around half this rate by age 75. 'Our data shows that the heart can generate new cardiomyocytes,' said Professor Frisén. 'I think this is exciting since it shows the possibility in the future to understand how this is regulated and potentially [to] try to modulate this regulation to stimulate the process of generation of cardiomyocytes, which could of course be beneficial after loss of cardiomyocytes, for example, after a heart attack.' He also highlighted the attractiveness of pharmaceutical therapies that could be introduced to activate the generation of these heart cells. Research that contributed to these findings has been accredited to scientists representing institutes in France and the US, as well as other Swedish research centres.

Countries

Sweden