Scientists identify genes that protect against atherosclerosis

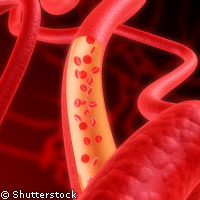

EU-funded scientists have identified a network of 37 genes that respond to lower cholesterol levels to prevent the accumulation of the plaques in our arteries that cause heart attacks and strokes. The results, which are published in the journal PLoS Genetics, could lead to the development of new treatments to prevent the build up of plaques in the first place. Atherosclerosis occurs when plaques build up on the insides of our artery walls, restricting the flow of blood to vital organs and causing heart attacks, strokes and even death. These plaques start to accumulate at a young age, and all adults have a certain degree of atherosclerosis in their major arteries. In industrial societies, atherosclerosis is the main cause of heart attacks and strokes, which between them cause almost half of all deaths. It is known that lowering levels of low density lipoprotein (LDL) or 'bad' cholesterol in the blood can slow down the accumulation of plaques and even cause them to become smaller. Currently, this is achieved by reducing cholesterol intake and by taking drugs known as statins. However, statins often cause severe side effects. In this latest piece of research, Swedish scientists studied mice which were prone to atherosclerosis to identify the genes involved in these processes. They found that atherosclerotic lesions develop slowly at first, then expand rapidly to form advanced lesions. However, by lowering blood cholesterol levels before the lesions were at an advanced stage, the researchers were able to stop the plaques from developing further. 'Our findings imply that the timing of interventions with plasma cholesterol-lowering agents may be very critical,' the scientists write. They suggest that patients at risk of developing complications of atherosclerosis, such as stroke and heart attack, could benefit from being treated very early in life. 'The development of non-invasive technologies to detect early atherosclerosis or molecular markers of atherosclerosis stages will be important in this respect,' they note. 'Previously, much atherosclerosis research was focused on identifying ways to stabilise the most dangerous plaques in order to prevent them rupturing and causing myocardial infarction or stroke,' explains Professor Johan Björkgren of the Karolinska Institute, who led the research. 'Our discovery means that we can now target the actual development of dangerous plaques.' The scientists also identified a network of 37 genes, which respond to lower cholesterol levels by working together to prevent the formation of advanced plaques. 'This network and the individual genes within it merit further attention as targets for drugs to prevent the transformation of early harmless lesions into advanced, clinically significant plaques,' the scientists state. 'The time when individual genes or gene pathways were thought to explain the development of complex common diseases, such as atherosclerosis, is past,' comments Professor Björkgren. 'We now have enough tools and knowledge of system biology to take on the total complexity of these diseases.' The work was supported by the EU-funded PROCARDIS ('Precocious coronary artery disease') project, which is financed through the 'Life sciences, genomics and biotechnology for health' thematic area of the Sixth Framework Programme (FP6).

Countries

Sweden