Energy-intensive sectors can be part of low carbon transition

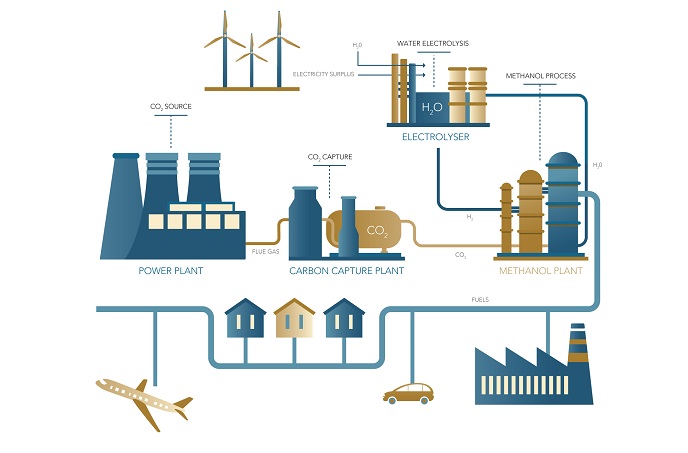

The MefCO2 (Synthesis of methanol from captured carbon dioxide using surplus electricity) project installed existing carbon capture and utilisation (CCU) technology at a coal-fired energy plant in Germany. This technology traps CO2 emissions and combines these with hydrogen in a process powered by renewable energy. This produces methanol, an industrial chemical that can be directly blended with gasoline or used as a building block for other chemical products like formaldehyde. Not only does this technique reduce the amount of CO2 being released into the atmosphere; it also creates a potential new business opportunity. “We’ve shown that CCU can be economically feasible,” says project coordinator Angel Sánchez-Díaz from I-Deals Innovation & Technology Venturing Services, Spain. “We were able to increase carbon capture viability from an economic perspective by using green hydrogen to produce a chemical of high industrial value.” CCU technology, says Sánchez, can help other energy-intensive industries such as the steel sector to transition towards the low carbon economy. Facilitating additional revenue streams from industrial by-products like this one is also very much in keeping with the circular economy concept of turning waste into new value-added products. Industrial challenges While achieving Europe’s climate goals will require significant industrial emissions reductions, access to cheap energy is important to guarantee competitiveness. The MefCO2 project demonstrated that European industry can be both greener and more competitive, and thus be part of the transition towards a low carbon economy. “Showing that CCU technology can deliver results in highly industrialised and complex settings is hugely significant,” says Sánchez. “There is enormous pressure on the energy sector as well as other energy-intensive industrial sectors, such as steel, to reduce their carbon footprint.” While a project partner had previously demonstrated that CCU technology can function at a smaller scale in Iceland, transferring the concept to Germany was daunting. “Look at the challenges facing Germany,” says Sánchez. “The country is committed to getting rid of nuclear power, focusing on renewables and meeting climate objectives, while at the same time remaining industrially competitive. It also has to deal with the fact that coal-fired power plants are still needed.” Low carbon transition As the project got underway, the technology first had to be adapted to meet the demands of the specific energy plant, and be integrated with the electricity grid. A catalyst to increase methanol synthesis efficiency was developed. “We really wanted to build a realistic case for CCU,” says Sánchez. “The challenge was demonstrating the technology in realistic working conditions.” With the pilot plant up and running, the consortium next put together a technology roadmap. “This is about how we can further scale up the technology and make possible the deployment of large-scale MefCO2-like plants,” says Sánchez. “We see the results of this project as just the first chapter of a story that has only begun, and MefCO2 partners will continue to work together in developing this technology.” Indeed, fostering cooperation has been a successful by-product of this project. “When you create the right working environment with different partners across Europe you are not only pursuing a common goal but creating a framework for future initiatives,” notes Sánchez. “Without European funding this would not have been possible, because businesses and industry need incentives. This project brought together the right ingredients and conditions to make this happen.”

Keywords

MEFCO2, energy, emissions, hydrogen, methanol, CCU, technology, coal