Integrated action to ensure healthy vines

Ochratoxin is a naturally occurring mycotoxin found in a wide variety of agricultural crops, including grapes. Viticulturists are constantly on guard for the presence of ochratoxin, as this can present a significant health threat. Many other agricultural commodities such as coffee, cereals, bread, cocoa, nuts, beer, wine, chocolate and spices can also be infected.

Difficulties in tackling ochratoxin

“Ochratoxin is produced as a byproduct of certain fungi,” explains OchraVine Control project coordinator Dimitris Tsitsigiannis from the Agricultural University of Athens. “This can be dangerous to health, and also very challenging to address.” One reason for this is that ochratoxin is produced by fungi at a time when grapes are full of sugar and close to harvesting. This makes treatment with fungicides extremely difficult, due to the risk of pesticide residues in the final product. Ochratoxins can also accumulate in raisins and currants when they are left to dry. Again, treatment with fungicides at this or a prior stage is extremely difficult.

Stopping fungus taking hold

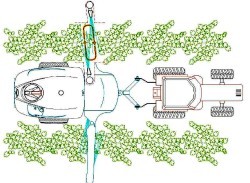

To overcome these challenges, the OchraVine Control project sought to find ways of stopping fungus from taking hold, and applying biological and synthetic plant protection products at the appropriate grape growth stage based on prediction models. The project was supported by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions programme. “We did this by combining digital technologies with smart integrated management strategies to prevent, control and minimise the risk of contamination in grapes, raisins and wine,” says Tsitsigiannis. “To do this, we first needed to know the conditions that favour fungal growth in the first place and be able to predict ochratoxin risk in vineyards.” The project carried out some fundamental research into exactly how a fungus named Aspergillus carbonarius invades and colonises certain crops. Environmental data, including data from weather stations, was then gathered and put into mathematical models and computer algorithms. These were designed to work out the potential level of risk posed to viticulturists. The project also investigated the most effective means of preventively treating crops. To do this, it evaluated combinations of biological products already on the market or novel ones discovered by the research group and evaluated these in vineyards in Greece. “Our goal here was to intervene as early as possible, and minimise the need for synthetic pesticides as much as possible,” adds Tsitsigiannis. A prototype decision support system pulled all this information together, providing farmers, via an app, with early warning information on the risk level posed by ochratoxins, and what combination of biological agents would be most effective.

Decision support system as a service

A project partner is currently looking to commercialise the decision support system as a service, and Tsitsigiannis believes that all technologies developed through the project could be brought onto the market in five to 10 years. Furthermore, he believes these will be very much needed. “Climate change will lead to temperature increases especially in southern Europe and northern Africa,” he notes. “This will increase the risk of ochratoxin contamination. So, the management of ochratoxins in the Mediterranean area is going to be very important.” Moving forward, Tsitsigiannis is interested in developing new biological control products that could one day replace synthetic pesticides, and employing sensors and satellite, drone or proximal imagery to detect crop diseases early. All these elements, he hopes, will eventually be brought to the market in an integrated, environmentally friendly solution leading to safer grape products.

Keywords

OchraVine Control, agriculture, viticulturist, ochratoxin, mycotoxin, fungi, pesticide