Toxicity can drive microbial species to cooperate

Microbes are model systems revealing much about ecology and evolution in larger organisms and with fast-growing populations, practical for lab study. They are also important organisms in themselves, supplying vital nutrients that some organisms cannot otherwise easily absorb – for example, vitamin K for certain animals (including humans) and nitrogen for plants. As microbes can be pathogenic, better understanding them could help reduce infectious diseases, alongside other microbe-dependent diseases, such as obesity. “While our survival is clearly intertwined with microbes, there’s still a lot that we don’t know, such as whether species compete or cooperate,” says Sara Mitri, project coordinator of the EVOMICROCOMM project, which was funded by the European Research Council.

A model system

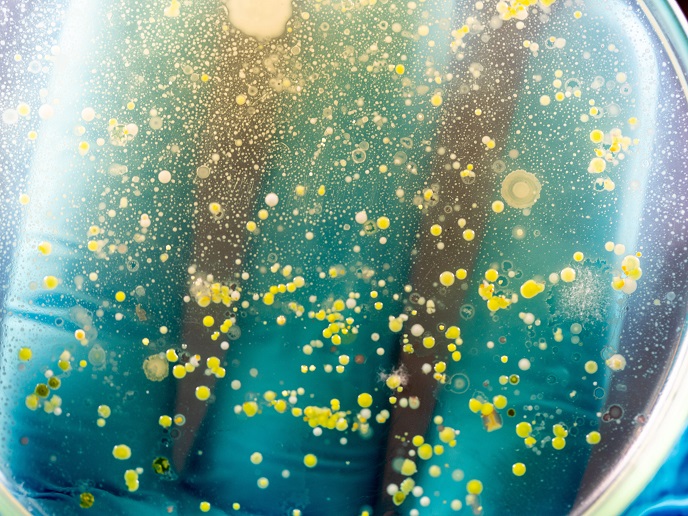

Microbes are difficult to study in their natural environment owing to the variety of species, and static lab environments are poor substitutes. EVOMICROCOMM developed a model system: comprising four species and using an industrial oil to resemble their natural environment. “This is one of the first studies to closely follow changing interactions between microbial species, shedding light on community co-evolution and environmental dependencies,” explains Mitri from the University of Lausanne, the project host. A key result was the discovery that microbial interactions are context-dependent, with toxic environments sometimes leading to positive interactions, if at least one species can degrade the toxins. “Our new community design is also potentially applicable to any microbial community, including compost and probiotic communities,” adds Mitri.

Competition or cooperation?

The team worked with four bacterial species: Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Comamonas testosteroni, Microbacterium saperdae and Ochrobactrum anthropi. These had previously been identified as able to grow in the industrial oil selected, metal-working fluid. As this industrial oil is regarded as a pollutant, understanding microbial ecosystems within it potentially has an important practical bioremediation application. “After we realised we could harness the oil’s toxicity as a feature, we observed that while microbes could not easily grow alone in toxic environments, they could as a community. If we always design growth media that all species can grow on, we might miss these interactions,” says Mitri. The team studied how toxicity levels shape microbial ecology. A single compound, toxic at high concentrations, seemed to prompt cooperation, but when reduced, species competition became the dominant interaction. In a second experiment, after a four-species community was left to evolve in the industrial oil, it was observed that after positive interactions had been maintained for a while, the community then cooperated to repel a new species introduced by the team. EVOMICROCOMM also showcased a new method to design microbial communities. Computational models that predict community growth rates in toxic conditions were first developed before experimentation with real communities. The algorithm predicted the optimum combination of species best at degrading pollutants in the industrial oil – two of the original species and two new ones. “Our breeding approach performs better than previous efforts, as it more easily swaps species around, expanding the range of possible compositions,” adds Mitri. .

Wide range of benefits

Learning how and which species benefit from toxic (to them) antibiotics could lead to more targeted treatments, countering the evolution of antibiotic resistance. And the project’s community designs are particularly useful for industrial processes to degrade compost or plastics, converting them into biofuels or other chemical products – topics the team is currently working on. “We have already been approached by labs interested in this area, as well as the conversion of plant fibres into ethanol,” concludes Mitri. Meanwhile the team is testing if their approaches could be applied to other ecosystems, again building, and testing mathematical models

Keywords

EVOMICROCOMM, microbial, antibiotics, cooperation, competition, toxic, bacteria, species, nutrients, oil, plastics