Ocean acidification puts deep-sea coral reefs at risk of collapse

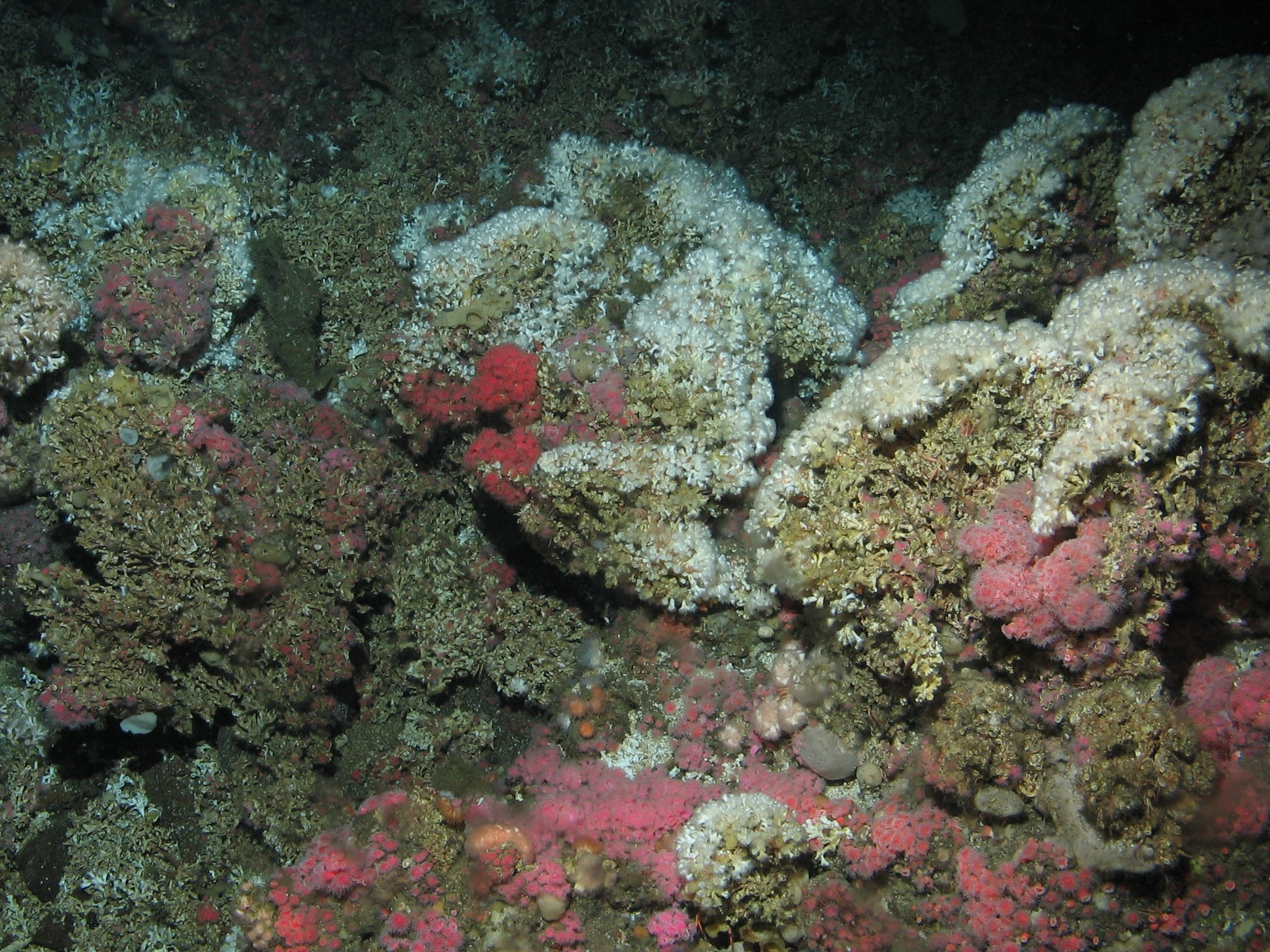

Scientists observed that the skeletons of dead corals, which support and hold up living corals, had become porous due to ocean acidification, and rapidly become too fragile to bear the weight of the reef above them. Previous research has shown that ocean acidification can impact coral growth, but the new study demonstrates that porosity in corals, known as “coralporosis”, leads to weakening of their structure at critical locations. This causes early breakage and crumbling that may cause whole coral ecosystems to shrink dramatically in the future, leaving them only able to support a small fraction of the marine life they are home to today. The findings complement recent evidence of porosity in tropical corals, but demonstrate that the threat posed by ocean acidification is far greater for deep-sea coral reefs. The study was led by University of Edinburgh scientists, together with researchers from Heriot-Watt University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and was funded by the EU ATLAS and iAtlantic projects, the Natural Environment Research Council, and NOAA. The team identified how reefs are becoming fractured by analysing corals from the longest-running laboratory studies, and by diving with submersibles off US Pacific shores to observe how coral habitat is lost as the water becomes more acidic. Dr Sebastian Hennige, of the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences, said: “Corals don’t just exist in the tropics. Deep-sea coral reefs are beautiful, fragile environments that play a vital role in the health and biodiversity of our oceans. This study highlights that a major threat to these wonderful ecosystems is structural weakening caused by ocean acidification, driven by the increasing amounts of carbon dioxide we produce. Our work highlights the vital importance of scientists from different disciplines and countries coming together to understand and tackle global challenges.” The corals in Southern California – on the most acidified reefs studied to date – are already experiencing the effects of climate change and exist in conditions that most deep-sea reefs are expected to encounter by the end of the century. Submersibles were launched from NOAA ships off Southern California and were guided by Dr Peter Etnoyer and graduate student Leslie Wickes. The US team sampled live and dead corals and returned them to the laboratory for experiments. The UK team applied engineering principles to demonstrate the rapid weakening of the skeletons and discovered a striking similarity to the weakening observed in human bones from osteoporosis. “By adapting strategies routinely used to monitor osteoporosis and assess bone fracture risk to instead understand coral reefs, we may have powerful non-invasive tools at our disposal to monitor these fragile ecosystems,” said Dr Uwe Wolfram of Heriot-Watt University. Tools developed as part of the project will aid understanding of when ocean ecosystems will change and how it will affect marine life. This will better equip society to deal with how these vulnerable ecosystems can be protected in the future, and will support the UN Decade of Ocean Science – which starts in 2021 – to deliver the science we need, for the ocean we want, the team says. Prof J Murray Roberts at the University of Edinburgh, who leads the ATLAS and iAtlantic programmes, said “Cold-water corals are truly the cities of the deep-sea, providing homes to countless other animals. If we lose the corals the city crumbles.” The research, published in the journal Frontiers of Marine Science, was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council, the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Grant Agreements 678760 (ATLAS) and 818123 (iAtlantic)) and NOAA, and supports increasing efforts to understand how reefs of the future will look, and what we can do to preserve them and the life they support. Publication: doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.00668 Contact for additional images/video