Opening up Europe’s written cultural heritage to people all over the world

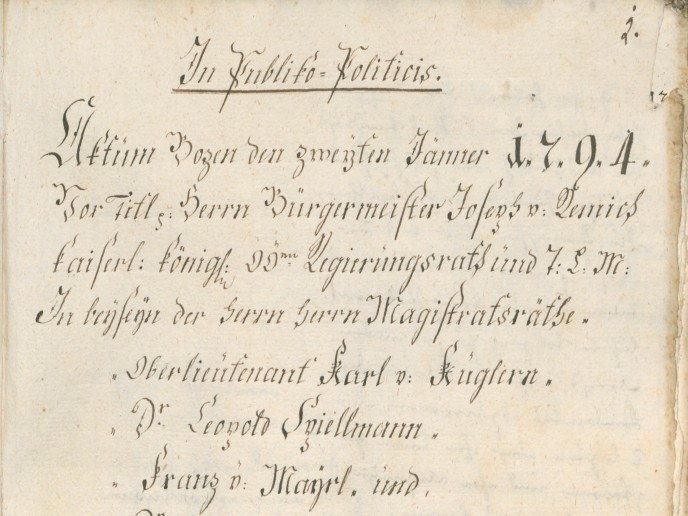

The READ project set out to implement a virtual research environment in which archivists, humanities scholars, computer scientists and volunteers could work together. The collective aim was the application of innovative technologies for the automated recognition, transcription and indexing of text to revolutionise access to historical documents. “We wanted to be able to explore and access hundreds of kilometres of archival documents via handwritten text recognition and by doing so, open up one of the last hidden treasures of Europe’s rich cultural heritage,” explains project coordinator Günter Mühlberger, head of the Digital Humanities Research Centre of the University of Innsbruck and a member of the Time Machine consortium. The project brought together several research groups and achieved scientific breakthroughs in fields such as handwritten text recognition, layout analysis and keyword spotting. According to Mühlberger: “Along with these breakthroughs, we have set up the first, handwritten text recognition platform called Transkribus where non-technical users can train their own networks to recognise specific scripts. More than 27 000 users are currently registered in the platform; hundreds of them use the platform daily.” Mühlberger is delighted to see how well the platform is being received by people working in areas as diverse as natural language processing and medieval history, saying: “Transkribus represents the largest training dataset of historical handwriting worldwide. Based on this overwhelming success we have set up one of the first European Cooperative Societies in the research and cultural heritage domain.”

Building on past work

READ was based on several previous projects, mainly Improving Access to Text and tranScriptorium in which the basic research was carried out. “One of the most important success factors, however, was that the e-Infrastructure programme for Virtual Research Environments gave us the chance to create a fully-fledged service,” Mühlberger adds. But however much of a head-start previous projects gave the team, there were still challenges to resolve, as is ever the case! One such challenge was what Mühlberger refers to as ‘the layout analysis problem’. When it comes to handwritten text recognition, the first step in the processing pipeline is that the computer needs to know where there is actually text on a page. This might look like an easy task, but it was the hardest challenge at the beginning of the project. “It was resolved by combining forces from several domains. First of all, a new concept of how to represent a line was introduced. Secondly, by far the largest dataset ever was created by integrating material from several archives. Finally, colleagues from the University of Rostock applied machine learning methods,” Mühlberger explains. Their multi-pronged approach paid off. The result was that from about 85 % accuracy in finding lines on a handwritten page, the rate was increased to about 97 % accuracy. The platform is gaining momentum. As Mühlberger says: “The National Archive in the Netherlands and the National Archives Finland started projects where millions of handwritten documents are made available via handwritten text recognition and keyword spotting to millions of users. These projects are among the first to be carried out with Transkribus and managed by the European Cooperative Society Transkribus.”

Keywords

READ, archival documents, full-text search, Transkribus, digitalisation, handwritten text recognition