Scientists investigate why people remain anxious

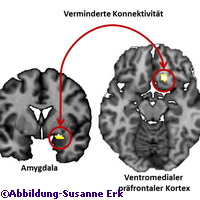

Is it easy to forget about anxiety after you face a traumatic event? Researchers in Germany have discovered it is not likely. In a new study, published in The Journal of Neuroscience, scientists at the Universities of Bonn and Berlin, in Germany identified a mechanism able to halt the process of forgetting anxiety after a stressful event. Feelings of anxiety do not diminish if not enough dynorphin is released into the brain, they said. Their findings could lead to the development of new therapies for trauma patients. Anxiety helps keep people out of trouble. This is even more obvious in people who have already encountered a stressful experience, compelling them to avoid fearful situations. However, the symptoms of fear usually subside when no other oppressive situation emerges. 'The memory of the terrible events is not just erased,' said lead author Dr Andras Bilkei-Gorzo from the Institute for Molecular Psychiatry at the University of Bonn. 'Those impacted learn rather via an active learning process that they no longer need to be afraid because the danger has passed.' However, various chronic anxiety disorders can develop following extreme physical stress triggered by wars, hostage-takings, accidents or catastrophes. So what makes one event more stressful than the other? Why are some events never forgotten but others gradually fade away from people's memories? 'We were able to demonstrate by way of a series of experiments that dynorphin plays an important role in weakening anxiety,' noted Professor Andreas Zimmer, Director of the Institute for Molecular Psychiatry at the University of Bonn. According to the researchers, the substance group in question is opiods, which include endorphins. Athletes release endorphins, which have both analgesic and euphoric effects. But dynorphins do the opposite; they mainly put a damper on emotional moods. The researchers tested the impact of dynorphins on subjects, discovering that anxiety symptoms persisted regardless of whether they were confronted with a negative stimulus over a longer time. They said a person will not forget a stressful incident like burning their hand on the stove, but learning vocabulary, meanwhile, is tedious but not tied to emotions. 'We took advantage of the fact that people exhibit natural variations of the dynorphin gene that lead to different levels of this substance being released in the brain,' said Professor Henrik Walter, head of the Research Area Mind and Brain at the Psychiatric University Clinic at the Charité in Berlin, who also used to conduct this type of research at the University Clinic in Bonn. The team split 33 healthy probands into two groups: one with the genetically stronger dynorphin release and the other which exhibited less gene activity. They said that probands with lower gene activity for dynorphin exhibited stress reactions lasting much longer than those probands that released much more. Brain scans showed that the amygdala, a structure found in the brain's temporal lobes and which processes emotional contents, was active as well. 'After the negative laser stimulus stopped this amygdala activity gradually became weaker,' said Professor Walter. 'This means that the acquired anxiety reaction to the stimulus was forgotten. This effect was not as pronounced in the group with less dynorphin activity and prolonged anxiety. But the "forgetting" of acquired anxiety reactions isn't a fading, but, rather, an active process which involves the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. In all likelihood dynorphins affect fear forgetting in a crucial way through this structure.'For more information, please visit:University of Bonn:http://www3.uni-bonn.de/University of Berlin:http://www.fu-berlin.de/en/The Journal of Neuroscience:http://www.jneurosci.org/

Countries

Germany