Sequenced seaweed genome help scientists unlock evolution puzzle

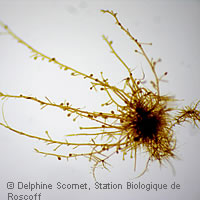

EU-funded scientists have sequenced and analysed the genome of a species of brown seaweed called Ectocarpus siliculosus. The findings, published in the journal Nature, shed new light on the evolution of multicellularity and reveal how seaweeds have adapted to the rigours of life in the harsh tidal environment. The EU supported the work through the MARINE GENOMICS ('Implementation of high-throughput genomic approaches to investigate the functioning of marine ecosystems and the biology of marine organisms') project, which received EUR 10 million under the 'Sustainable development, global change and ecosystems' Thematic area of the Sixth Framework Programme (FP6). Brown seaweeds are of interest to scientists for a number of reasons. Firstly, they are one of just five groups of organisms to feature complex, multicellular life forms, the others being animals, plants, fungi and red seaweeds. Secondly, as a result of their unusual metabolisms, brown seaweeds produce a number of molecules which attract diverse industries. For example, polysaccharides from brown seaweeds are already used in the pharmaceutical, food and textile industries, and recent research has revealed that brown seaweeds produce a molecule that stimulates crop plants' natural defence systems. E. siliculosus grows up to 20 centimetres (cm) long, is closely related to kelp, and can be found on rocky shores in temperate climes worldwide. Its genome is 214 million base pairs long and features over 16,000 genes. Scientists believe that animals, plants, fungi, red seaweeds and brown seaweeds each evolved multicellularity independently. Nevertheless, analyses of the brown seaweed genome reveal that it appears to employ many of the same molecular 'tricks' to achieve multicellularity as plants and animals. 'In the brown alga, we found many genes for so-called kinases, transporter and transcription factors,' commented Klaus Valentin of the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, one of the authors of the paper. 'Such genes are also commonly found in land plants, and we suspect that they also play a key role in the origin of multicellular organisms.' The scientists were also keen to explore how E. siliculosus' genes help it thrive in the difficult coastal environment. 'The shallow waters of the intertidal region are an attractive habitat for marine, sedentary, photosynthetic organisms providing them with both a substratum and access to light,' the researchers write. 'However the shoreline is also a hostile environment necessitating an ability to cope with tidal changes in light intensity, temperature, salinity and wave action.' According to the team, 'Several features of the Ectocarpus genome indicate that this alga has evolved effective mechanisms for survival in this environment.' For example, it appears to have a complex photosynthetic system that allows it to adapt to the large variations in light conditions that it experiences as the tide rises and falls. It also boasts compounds that offer protection against ultraviolet radiation and enzymes that help it cope with the stresses of its coastal home. 'In the context of climate change, we have now become interested in how brown algae have adapted to UV light and increasing temperatures,' commented Dr Valentin. 'In addition, brown algae are evolutionary speaking much older than terrestrial plants. They have multiple metabolic properties, but these have barely been studied. A better understanding of the properties locked up in the genes could also be a foundation for the development of new products and technologies.'