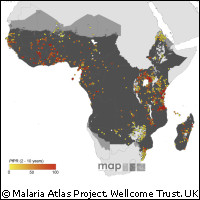

New malaria map reveals extent of disease burden

A new global malaria map reveals that just over a third of the world's population is at risk of contracting the deadly disease. However, the good news is that for many of these people, the risk is much lower than was previously believed. This means that for these people, simple tools such as mosquito nets could help to eliminate the risk entirely. Around 500 million people contract malaria every year, and a million of these, mostly young children in sub-Saharan Africa, die of it. The majority of these deaths are caused by a parasite called Plasmodium falciparum, which is transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes. Recent years have seen malaria climb up the development agenda, and large amounts of money have been made available to help control it in countries where the disease is endemic. As a result, there has been an increase in access to effective drugs and prevention strategies in a number of countries. Allocating precious resources to combat malaria requires an understanding of the geographical distribution of malaria risk. However, the last detailed map of malaria risk was put together some 40 years ago, meaning a new map was urgently needed. In this latest study, an international team of scientists working on the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP) created a new global map showing where the risk of P. falciparum transmission is moderate or high, and where it is low. To do this, they consulted national health information systems and nationally reported malaria statistics and carried out detailed surveys of malaria infection in nearly 5,000 communities worldwide. They also fed into their system data on the climatic conditions which affect the parasite's survival. For example, below a certain temperature, infected mosquitoes die before the parasites have reached the stage in their life cycle where they are ready to be injected into humans. The team's results are published in the open access journal PLoS Medicine. The map reveals that 2.37 billion people (35% of the world's population) are at risk from P. falciparum, most of them in Africa and south and east Asia. However, for 1 billion of these people, the risk of transmission is much lower than had previously been assumed. The zone where the risk is reduced covers central and south America, Asia and even parts of Africa. 'We were very surprised to find a significant number of people were facing a much lower risk than was previously thought,' commented Dr Simon Hay of the University of Oxford. 'Of course, this does not mean that malaria is any less of a problem, but it gives us hope that eliminating the disease from certain regions may be achievable using tools as simple and cost-effective as insecticide-treated bed nets.' The map also highlights the difficulties linked with attempts to eradicate malaria. Saudi Arabia is providing significant funding to anti-malaria programmes in neighbouring Yemen. However, the new research shows that even if malaria is eliminated from Yemen, the high numbers of people arriving in Yemen from Somalia mean the risk of the parasite being reintroduced to the country will remain high. Ultimately, scientists hope their work will help donors and funding agencies target their investments more effectively. 'It's reasonable to think we can reduce or interrupt transmission in many places, but the prospects for success will improve if we make plans that are based on good information about malaria's distribution,' explained David Smith of the University of Florida.